http://www.unodc.org/pakistan/en/report_1999-06-30_1.html

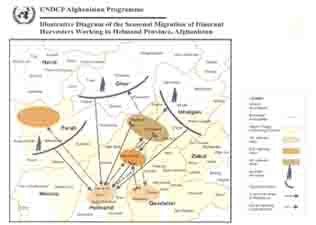

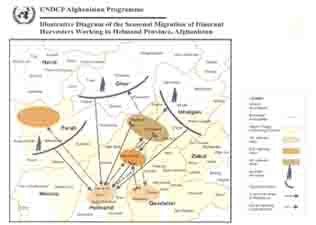

| 4. The source of itinerant harvesters Fieldwork suggests that itinerant harvesters in Helmand in 1999 came from a wide range of areas within Afghanistan and from a number of refugee camps from across the border in Pakistan (see Table 1). In total, respondents travelled from ten different provinces in Afghanistan to work as itinerant harvesters in Helmand, including provinces in the north, south, and central regions.

Yet despite this diversity, almost 70% of the itinerant harvesters interviewed came from just two provinces, Ghor and Helmand itself (see Map on inside cover).

Respondents from Helmand came from seven districts. Most of the major opium poppy producing districts from both lower and upper Helmand were represented, including Baghran, Nawzad, Nad-e-ali, Nahr-e-Saraj, and Marja (see Table 2). The timing of the opium poppy harvest across the districts of Helmand generally varies with the different altitudes and climatic conditions present, allowing itinerant harvesters to travel between districts and conduct as many as three harvests within the province. Indeed, 80% of respondents from Helmand were found to cultivate opium poppy in their own districts and, during periods of agricultural underemployment on their own land, worked as itinerant harvesters in other districts within the province. Almost 40% of the respondents who resided in Helmand Province came from Baghran. The late harvest and small landholdings in Baghran would seem to explain the prominence of respondents from this area amongst those interviewed.

Table 1: Province of permanent residence of itinerant harvesters interviewed

|

Helmand

|

28

|

Ghor

|

23

|

Balochistan

|

5

|

Oruzgan

|

5

|

Qandahar

|

3

|

Farah

|

2

|

Kabul

|

2

|

Nimroz

|

2

|

Wardak

|

2

|

Badghis

|

1

|

Zabul

|

1

|

Kutchi

|

1

|

| Total |

75

|

|

Table 2: District of permanent residence of itinerant harvesters interviewed from Helmand Province

|

Baghran

|

11

|

Musa Qala

|

4

|

Nawzad

|

3

|

Nadeali

|

3

|

Nahr-e-Saraj

|

3

|

Marja

|

3

|

Sarban Qala

|

1

|

Total

|

28

|

�

|

Table 3: District of permanent residence of itinerant harvesters interviewed from Ghor Province

|

Pasaband

|

11

|

Shahraq

|

5

|

Taiwara

|

4

|

Chaghcharan

|

2

|

Tulak

|

1

|

Total

|

23

|

�

|

All the respondents who reported that they resided in Ghor province reported that they were Taimani.11/ They came from 5 districts, including Pasaband, Taiwara, Chaghcharan and Sharaq. The three districts closest to Helmand, Pasaband, Sharaq and Taiwara were the source of 20 of the 23 respondents interviewed from Ghor (see Table 3).

The great majority of respondents from Ghor owned land and after the completion of the opium poppy season in Helmand, reported that they would travel back to Ghor to harvest their rainfed wheat. A number of the Taimani respondents reported that they not only worked in Helmand during the opium poppy harvest but during the poppy weeding season from January until March, as well.

Those respondents who had travelled from other provinces to work in Helmand typically came from opium poppy cultivating districts. Indeed, aside from those interviewed from Ghor and Balochistan, only six respondents resided in districts that did not cultivate opium poppy, including Shiwaki in Kabul province and Chak-e-Wardak, in Wardak province. Consequently, in total 55% of respondents were found to come from opium cultivating districts.

However, it is important to recognise that it is not necessarily familiarity with opium cultivation within the district of residence that acts as the motivation for individuals to work as itinerant harvesters in other districts. Indeed, fieldwork has revealed that it is often the experience individuals obtain as itinerant harvester that can result in an area becoming an opium cultivating district. For instance, two respondents who resided in Shindand in Farah province reported that they would return to the district to work as an itinerant harvester in their own village after completing the opium poppy harvest in Helmand. Fieldwork for both the Annual Opium Poppy Survey for 1999 and the final phase of Strategic Study 1: An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation into New Districts in Afghanistan has revealed that opium poppy cultivation has begun in Shindand in the 1998/99 growing season and itinerant harvesters working in Helmand would appear to be a major cause of its cultivation in the district.12/ Fieldwork in the districts of Logar, Mehtarlam and Qargahayi in the eastern region of Afghanistan has produced similar findings.13/

The majority of respondents were from the Pashtoon tribes, including Alizi, Noorzi, Popalzai, Alikozai and Khogiani. Pashtoon respondents were from a variety of tribes with no one tribe dominating. The number of provinces from which respondents came from and the resettlement of different tribes in the canal area of lower Helmand during the 1960's and 1970's probably explains the diversity of Pashtoon tribes represented amongst those interviewed. Apart from the Pashtoons and the Taimani from Ghor, only one Tajik and one Baloch were found amongst the 75 respondents. Even the respondent from Badghis in the north, was from the Hotak tribe of the Pashtoons.

5. The socio-economic status of itinerant harvesters

Almost two thirds of respondents interviewed for this Study reported that they owned land in their districts of residence. Landholdings amongst these households varied from less than one sixth of one hectare to four hectares, with an average of four fifths of one hectare. The highest incidence of landownership was amongst those respondents who came from Ghor where almost 85% were found to own land in their districts of residence. However, the vast majority of this land was reported to be of a limited size and rainfed, severely constraining its productivity (see Box 1).

Whilst a further 10% of respondents indicated that they were landless but were employed as sharecroppers in other districts within Helmand province, one quarter of those interviewed reported that they had no land at all. Those respondents without land indicated that when they were not working as itinerant opium poppy harvesters they earned their livelihoods through off-farm and non-farm income earning opportunities, including animal husbandry, and brick making and construction. Indeed, whilst the majority of respondents indicated that they had travelled from their district specifically to obtain work on the opium poppy harvest, a number of respondents reported that they had only taken work in the opium poppy fields due to their failure to find wage labour opportunities in the local area.

Box 1

The Group from Ghor: A 36 year old man from Sharaq district, Ghor province was interviewed whilst harvesting opium poppy in Marja district in Helmand Province. He indicated that he had three fifths of a hectare of land in Ghor which was cultivated with rainfed wheat. He claimed that the production from his land was insufficient to satisfy his household?s basic needs. He claimed that this was common in his village, and that he was one of a group of 12 people that had travelled to Marja from his village, in search of work as itinerant harvesters. The respondent claimed that the youngest of the group was 13 years of age and was his son. The group had reportedly travelled directly to the main bazaar in Marja where they had been recruited by a local landowner. He reported that they had received one fifth of the final opium yield and that the cost of the ushr had been shared by the landlord and the itinerant harvesters. His share of the opium was 1.5 kg which he subsequently sold in the local bazaar for $45, purchasing wheat and clothes with the proceeds. The respondent claimed that from Marja, the group would travel to Kajaki and then to Baghran for a final harvest, before travelling back to their own village to harvest their wheat crop. He suggested that there were few alternative sources of livelihood for his family and for this reason he had been migrating to Helmand to work as an itinerant harvester during the opium poppy season for the last seven years. |

|

|

Six of those respondents without land were students who claimed that they wished to continue their studies and were merely working during the opium poppy harvest to support their families and the cost of their studies. Four of these respondents were from refugee camps in Balochistan, Pakistan whilst the remaining two were from madrassas in Musa Qala and Kajaki. Indeed, during the time of the fieldwork in Helmand many of the madrassas were found to be empty due to the number of students working as itinerant opium poppy harvesters.

This finding is supported by the fieldwork for the Socio-Economic Baseline Survey which suggested that 35% of respondents with sons attending the madrassa removed them during the period of the opium poppy harvest.14/ Moreover, a number of respondents and key informants have reported that both students and teachers were actively engaged in the harvesting of opium poppy in both the eastern and southern regions of Afghanistan in 1999. Indeed, one of the respondents from Ghor reported that he was the village mullah.

Amongst those respondents that owned land there was a general consensus that their land was insufficient to cater for their basic needs. For instance, one respondent from Ghor indicated that sixteen family members were dependent on one fifth of one hectare for their direct entitlement. Given these constraints respondents reported that they, and other male family members, sought short term labour opportunities in other districts and provinces during times of agricultural underemployment in their own area. Indeed, both those respondents who indicated that they owned land in their districts of residence and those who sharecropped land, reported their work as itinerant harvesters was timed around the harvest of their own crops.15/

�

11/ The Taimani are one of the four Aimaq tribes. They occupy the south western portion of the Ghor mountains between Herat and Farah. For more details on the Taimani see Bellew (1891) An Enquiry into the Ethnography of Afghanistan. Vanguard Books: Lahore.

12/ The final report for Strategic Study 1:� An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation into New Districts in Afghanistan will be based on fieldwork in approximately 12 districts from each of the main opium regions in Afghanistan, including the north. It is expected to be available by September 1999.

13/ See Strategic Study 1: An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation into New Districts in Afghanistan (Preliminary Report, July 1998).

14/ See Socio-Economic Baseline Survey for UNDCP Target Districts in Afghanistan(forthcoming).

15/ These findings would see to be supported by Afghanaid's fieldwork in Saghar and Teywara in Ghor which suggests that 'there are no off-farm income sources locally, young men and boys migrate seasonally to neighbouring provinces and countries looking for employment and remit income to their homes'. See Afghanaid (1998) A Baseline Survey Report: Chaghcharan, Teywara and Saghar Districts, Ghor Province. Afghanaid: Peshawar.

|

|

|

| 6. The age and gender of itinerant harvesters Based on the reports of both respondents and key informants it would seem that itinerant harvesters are typically young and male. The fieldwork for this Study revealed that the average age of respondents was 24, with a range from 10 years of age to 55. However, almost half of those interviewed were under 20, whilst only 16% of respondents were 35 years or older.

Analysis suggests that on average respondents began work as itinerant harvesters at 20 years of age. However, 60% of respondents indicated that they had first harvested opium when they were less than 20, whilst less than 10% reported that they first harvested opium at 35 years or older. It is noticeable that the average age at which those respondents emanating from Helmand reported that they first began harvesting opium poppy was 17 years of age, compared to 23 years of age amongst those from Ghor.

Fieldwork suggests that respondents had been harvesting opium for an average of 4 years. Indeed, almost 75% of those interviewed had been working as itinerant harvesters for less than five years whilst only 6% of respondents had been harvesting opium poppy for more than ten years. One fifth of those interviewed, reported that 1999 was their first year of harvesting opium poppy on a wage labour basis.

Without exception itinerant harvesters in Helmand were found to be male. Indeed, during three weeks fieldwork in five districts, only one female was seen working on the opium poppy harvest. This female was only 11 and was a member of a landless household that was sharecropping in Kajaki. According to her father she was assisting in the harvest of opium poppy so that the household could avoid hiring labour and, subsequently, increase the profit that they accrued from their crop.

The absence of female labour during the opium harvest in the south differs markedly from the eastern region where women can be seen actively engaged in household opium collection. Moreover, whilst rare, female itinerant harvesters have been witnessed working with their spouses close to Jalalabad city.16/

However, it is important to recognise that even in the southern region the opium poppy harvest is a labour intensive time for women as well as men. There was a general consensus that three good quality meals and tea are a standard part of the payment for itinerant harvesters. Given the size of the hired workforce, the preparation of this food and drink is reported to increase the work of women significantly. Indeed, one household in Kajaki indicated that it employed a local widow purely to assist in the preparation of food during the opium poppy harvest.

7. The technical knowledge of itinerant harvesters

The exact timing of the opium poppy harvest is determined by the variety of the opium poppy cultivated, the time of sowing and most importantly climatic conditions in the district. Consequently, the timing of the harvest in any one district may differ by a number of days from one year to the next. For instance, the harvest in Nawzad was reported to begin ten days earlier in 1999 than it had in the previous year due to particularly warm weather.

For those respondents who had worked as itinerant harvesters before, their past experience of working in different opium producing districts was used to determine when the opium poppy harvest would begin in each of the districts they intended to work. Those respondents that were working as itinerant harvesters for the first time relied on the information of family and friends. Indeed, to determine the exact time of the harvest in any particular district, traders and relatives working in the district on a long term or seasonal basis, were the main sources of information cited by respondents.

Given the short duration of the opium poppy harvest in any one area, landowners are keen to identify skilled itinerant harvesters. Indeed, key informants suggest that the landowner prefers to select experienced lancers and will recruit itinerant harvesters� that have worked on his land before, if they are available. Fieldwork revealed that this selection criteria can result in inexperienced labourers not finding work unless someone is willing to vouch for them and provide training. Most respondents reported that they had learnt how to lance and collect opium from either their relatives or friends. For those who came from opium producing districts, their first experience of harvesting opium poppy was in their own district and generally on their own land under the tuition of their relatives. Those respondents that did not come from opium producing districts typically conducted their first harvest in Helmand.

Generally, those travelling long distances to work on the opium harvest were found to work in groups. Those travelling from either Ghor, Oruzgan or the refugee camps in Balochistan were rarely found to be working individually. Key informants reported that these groups were often formed in local mosques and consisted of between 5 and 20 people. According to respondents the age of the members of each group ranged from 10 to 55. Respondents reported that those within the group who had previously worked as itinerant harvesters provided training in the lancing and collection of opium for those who were inexperienced. Generally, those travelling long distances to work on the opium harvest were found to work in groups. Those travelling from either Ghor, Oruzgan or the refugee camps in Balochistan were rarely found to be working individually. Key informants reported that these groups were often formed in local mosques and consisted of between 5 and 20 people. According to respondents the age of the members of each group ranged from 10 to 55. Respondents reported that those within the group who had previously worked as itinerant harvesters provided training in the lancing and collection of opium for those who were inexperienced.

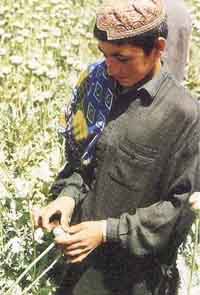

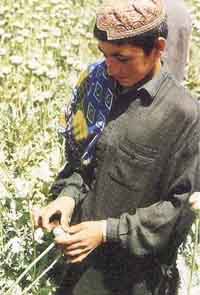

Indeed, respondents reported that the identification of mature opium poppy capsules and incising the capsule appropriately, required some experience to ensure that the maximum yields were obtained. For instance, lancing opium capsules prior to full maturation is thought to significantly effect the final yield. Consequently, to identify mature capsules, each capsule is tested by the harvester by squeezing them between thumb and forefinger prior to lancing. To the inexperienced the difference between a mature and an immature capsule would appear negligible.

The depth of the incision during each lance is also thought to significantly effect the final yield. If the incision is too deep the skin of the capsule will be cut and the latex will oxidise in the capsule, if the incision is too shallow and the flow of the latex will be constrained. However, the membrane of the capsule toughens as it matures over the period of the harvest. Given that the duration of the harvest may be from 15-20 days, with as many as six lances, deeper incisions have to be made to extract the opium during the latter stages of the harvest. Consequently, as many as three different lancing instruments, known as neshtars, each with different length blades, are used by experienced harvesters in the Helmand area.

�

16/ The male of this elderly couple was interviewed during earlier fieldwork in 1998 and revealed that due to their age and restrictions on the mobility of women they limited their work as itinerant harvesters to a very localised area in which they had worked for a number of years.

|

|

|

| 8. The recruitment of itinerant harvesters The sheer amount of labour required to lance the opium poppy capsule and collect the gum means that the majority of opium poppy producing households are required to hire labour during the harvesting period. Indeed, previous fieldwork revealed that 70% of those opium producing households interviewed in UNDCP's target districts of Ghorak, Khakrez, Maiwand and Shinwar, hired labour during the opium poppy harvest.

The number of itinerant harvesters required by the landowner will ultimately depend on the size of the field to be harvested, the number of lances that will be conducted, and the availability of other sources of cheap labour, including family and sharecropping labour. Therefore, in order to obtain sufficient labour to harvest their opium poppy some landowners may employ a collection of individuals or one or more groups of itinerant harvesters. The result is there are often itinerant harvesters from a number of different provinces working together in the same field along with relatives and sharecroppers.

Both respondents and key informants reported that the recruitment of itinerant harvesters tends to be conducted at the district bazaar. Therefore at the point at which the harvest is due to begin in any district, those wishing to be employed as itinerant harvesters congregate at the district centre.

Key informants suggest that the landowner's preference is for skilled itinerant harvesters due to the short harvesting period for opium poppy and the losses that can be incurred due to poor lancing. The result is that those without experience may find it difficult to obtain work as an itinerant harvester unless they have an experienced harvester who is willing to support their recruitment. In Nawzad, landowners were witnessed delegating the entire recruitment process to experienced itinerant harvesters. Moreover, the influx of labourers into Nawzad due to the payments being offered, reportedly led to limited opportunities for employment for inexperienced itinerant harvesters. Indeed, Nawzad is the only district in which none of the respondents were working as itinerant harvesters for the first time in 1999.

Prior to employment an agreement is reached between the landowner and itinerant harvesters. These agreements concern the duration of the harvest, the exact number of lances to be undertaken, and the nature and amount of the payment that will be made by the landowner. Key informants reported that if it becomes obvious to the itinerant harvesters that the yield from the crop will be poor and therefore their final payment lower than expected, it is not possible for them to abandon the crop. The agreement made between the two parties is considered binding and both are committed to fulfilling their obligations under it. It is reported that both informal village institutions and more formal bodies, such as the local authorities, will enforce an agreement if necessary.

Few respondents reported that they worked for the same landowner each year. Indeed, the variance in the time of the harvest of opium poppy each year and the demands of respondents own agricultural land would seem to mitigate against such habitual arrangements. Consequently, recruitment would seem to be more of a function of the time of the opium poppy harvest in the district, the availability of itinerant harvesters, and the results of the negotiation between landowner and itinerant harvesters, than traditional links based on family, tribe or friendship.

9. The mobility of itinerant harvesters

Fieldwork reveals that itinerant harvesters are typically mobile, timing their travel between districts to coincide with the staggered nature of the opium poppy harvest within Helmand province (see Map on inside cover). Indeed, only 10% of respondents reported that they harvested opium in one district. Almost two thirds of respondents were found to harvest in two districts, whilst one quarter indicated that they harvested in three districts. Only one respondent reported harvesting in four districts, travelling from Marja to the higher areas of Deh Rawud in Oruzgan, during the harvest period.

The opium poppy harvest typically begins in the southern parts of Helmand in the districts of Marja, Nahr-e-Saraj and Nad-e-Ali. Consequently, many respondents began their work on the opium harvest in these districts. Typically those respondents who resided in Helmand province who were working as itinerant harvesters in Marja and Nad-e-Ali were landless or from Baghran in upper Helmand.Few of the respondents interviewed in Marja and Nade-e-Ali were found to be from the Kajaki, Musa Qala, or Nawzad. Indeed, respondents from these three districts were generally found to conduct their first harvest in Musa Qala, Nawzad or Kajaki, often on their own land, before travelling north to Baghran to undertake a second and final harvest.

Those respondents who were found to conduct the opium harvest in three separate districts were from Marja, Nad-e-Ali and Baghran, in Helmand province and Oruzgan or Ghor. Those from lower Helmand typically began the opium poppy harvest on their own land before travelling north to conduct a second harvest in Musa Qala, Kajaki or Nawzad. Their final harvest of the year would be in the most northern reaches of Helmand in Baghran. Similarly, those respondents from Baghran followed a similar route before completing the harvest on their own land in northern Helmand (see Box 2). The respondents from Oruzgan travelled from southern Helmand to Kajaki, Musa Qala or Nawzad before travelling eastwards to Deh Rawud or Tirinkot to complete the harvest in their own village. Due to the timing of the opium poppy harvest in Baghran approximating that in Oruzgan, none of the respondents from Oruzgan reported working as itinerant harvesters in the upper reaches of Helmand province.

Generally respondents from Ghor moved from the first harvest in southern Helmand northwards to Kajaki, Nawzad or Musa Qala before conducing a final harvest in Baghran. After completing the harvest in Baghran, respondents from Ghor travelled north, returning to their own land, typically to harvest their rainfed wheat. Indeed, respondents from Ghor reported that they had typically focused their work as itinerant harvesters in Helmand in previous years. None of those interviewed reported that they had worked in either Oruzgan or Qandahar, although UNDCP field staff have encountered Taimani harvesters in UNDCP's target districts of Maiwand and Ghorak in Qandahar province. However, fieldwork suggests that respondents from Helmand were more mobile working in a number of different provinces, including Helmand, Qandahar and Oruzgan.

| Box 2 The Sharecropper from Baghran: A twentyfive year old man from Baghran in northern Helmand was interviewed in Kajaki district, Helmand Province. He reported that he had travelled to Kajaki from Gereshk after completing his first harvest of 1999. He claimed that in Hereshk he had received one fifth of the final opium yield from the landowner compared to one quarter in Kajaki. Moreover, he reported that in Gereshk the ushr� on the harvest was shared between landowner and itinerant harvester, whilst in Kajaki the landowner had agreed to meet the entire cost of the tax. He reported that upon completing the harvest in Kajaki he would return to his land in Baghran to assist his brother in harvesting their opium poppy. His brother was currently tending to their land in Baghran whilst he was working as an itinerant harvester. He claimed that the opium that he had earned in Gereshk had been sold in the district itself, whilst he thought the opium he would earn in Kajaki would be sold in Musa Qala bazaar on his route back to Baghran. He reported that he would use the proceeds from his work to purchase clothes and wheat for family consumption.

|

|

|

Despite mobility within the region, few respondents reported that they had worked as itinerant harvesters in any of the other main opium poppy producing regions in Afghanistan. Indeed, only one respondent had worked as an itinerant harvester in the eastern region, harvesting opium poppy in Nangarhar. This respondent reported that he was from Kabul and was employed as an itinerant harvester in a village in Marja where his father was the local mullah.

It is important to recognise that for almost one third of respondents reported that they would be returning to their own land to harvest opium at some point during their travel between the different opium poppy producing districts. Moreover, 72% of respondents indicated that they would be returning to their own land to tend to their own crops, many foregoing the possibility of working as an itinerant harvester in another opium producing district. For instance, many respondents from Helmand reported that they would be returning to their own land to plant their summer crops, in particular maize and mung beans, rather than conduct another harvest in the province.

This tendency to give priority to household agricultural production over wage labour opportunities would suggest that the income earned from working as an itinerant harvester is merely an important supplement to household production rather than a substitute for it. Indeed, whilst most respondents reported that they tended to work as itinerant harvesters each year, they indicated that the number of districts that they would work in would depend on the demands of their own agricultural land and whether their household production could meet their family needs.

| 10. The payment for itinerant harvesters Typically, the payment for itinerant harvesters in Helmand comprises of a payment in-kind, a bonus, if the yield of the opium crop is particularly high, and transportation. All these three elements of payment are negotiable and will depend on the bargaining power of the landowner and itinerant harvesters, respectively. The arrangement for the payment of local agricultural taxes, known as ushr, is also negotiable and proved to be an important part of contractual arrangements in the districts of Kajaki, Musa Qala and Nawzad in 1999. The provision of three good quality meals for itinerant harvesters is, however, non-negotiable and is considered a standard part of the agreement by both parties.

All respondents reported that they would be paid for their work on the opium harvest in-kind. However, both respondents and key informants reported that there are two forms of payment in-kind that are available to itinerant harvesters in Helmand. The first and most frequently used method of payment is a share of the final yield of the land worked. In 1999, itinerant harvesters in Helmand typically received one fifth or one quarter of the total opium yield, compared to one sixth to one fifth in 1998, possibly supporting the view that opium cultivation in Helmand has increased significantly in the 1998/99 growing season.

To determine the total yield of the opium poppy crop, the opium collected is weighed at the end of each day and a note of the amount is taken by both itinerant harvesters and the landowner. This account is the basis by which the final yield is calculated and divided amongst the different parties.The other method of payment in-kind cited by respondents was the payment of a fixed amount of opium for a given amount of land and number of lances conducted. For, instance one respondent reported receiving 2.25 kg for 13 days work, equivalent to the value of $70 at harvest time. Key informants suggest that the risk of a poor crop means that itinerant harvesters prefer to receive a fixed amount of opium as payment for their work rather than a share of the final crop. Moreover, it is argued that a fixed payment, based on an agreed number of lances, offers itinerant harvesters the opportunity to complete their work in only 15 days, as opposed to the 16-20 days that itinerant harvesters receiving a share of the final yield tend to be committed to.

Amongst the respondents interviewed there were only four cases where itinerant harvesters were paid a fixed amount. Two of these cases were for the only respondents who reported that they were working as itinerant harvesters for relatives or friends (see Box 3).

| Box 3 The Student from Girde Jungle, Balochistan:A 16 year old boy was interviewed harvesting opium in Marja district, Helmand Province. The boy reported that he was a student in the eighth grade in a school in Girde Jungle refugee camp, Balochistan, Pakistan. The boy was working on his uncle?s land on a contract basis, receiving a fixed amount of 2.25 kg of opium for 15 days work. He indicated that he would sell the opium he earned in Marja district in Lashkargah bazaar, Bust, before travelling to Nowzad to complete a second and final harvest. He indicated that he was working as an itinerant harvester to assist the household meet their basic needs as well as to finance his future studies.

|

|

|

Key informants reported that landowners preferred to pay itinerant harvesters a share of the final yield of the land worked rather than a fixed amount, believing that this method of payment compelled itinerant harvesters to work harder due to their shared ownership over the final output, and that it allowed the risk of crop failure to be shared with the itinerant harvesters.

Field work revealed that the majority of respondents were paid a share of the final yield of the land worked. However, it is noticeable from the reports of respondents that the share of the final yield changed with the onset of the harvest in Kajaki and Musa Qala. It is reported that the early harvest in Nawzad created a local labour shortage, forcing up the share of the final yield received by itinerant harvesters, from one fifth to one quarter not only in Nawzad but during the later stages of the harvest in Nad-e-Ali, and throughout the harvest period in Kajaki and Musa Qala.

The extent of the labour shortage in upper Helmand, is perhaps verified by the general consensus amongst respondents that landowners in the districts of Kajaki, Nawzad and Musa Qala had covered the entire cost of the local agricultural tax, known as ushr, whilst in the districts of Marja, Nade-e- Ali, and Nahr-e-Saraj this payment was typically shared by itinerant harvester and landowner.

Key informants suggested that the local authorities suggested that itinerant harvesters should not be paid more than one quarter of the final harvest, despite reports of this local labour shortage. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this policy was based on the judgement that the share accrued by itinerant harvesters working for only 15-20 days should not exceed that of sharecroppers, labouring for the entire season.

�

Table 4: Proportion of a yield of 100 kg accrued by landowner and itinerant harvester

(kilogrammes of opium)

|

| � |

Itinerant Harvester Receives

1/5 of Final Crop�

|

Itinerant Harvester Receives

1/4 of Final Crop�

|

| Proportion of total yield when cost ofushr is shared by landowner and itinerant harvesters� |

Proportion of total yield when cost ofushr is paid by landowner� |

Proportion of total yield when cost ofushr is shared by landowner and itinerant harvesters� |

Proportion of total yield when cost ofushr is paid by landowner� |

| Total Yield |

100 kg |

100 kg |

100 kg |

100 kg |

| Ushr |

10 kg |

10 kg |

10 kg |

10 kg |

| Landowner |

72 kg |

70 kg |

67.5 kg |

65 kg |

| Itinerant Harvesters |

18 kg |

20 kg |

22.5 kg |

25 kg |

Key informants have suggested that the landowners willingness to pay the full amount of the ushr in Musa Qala and Kajaki was a means by which to ensure the availability of itinerant harvesters and circumvent the local authorities reported decree that itinerant harvesters should not be paid more than one quarter of the final opium yield from the land worked. For a total yield of 100 kg of opium, the landowners agreement to pay the entire cost of ushr could be worth as much as an extra 2.5 kg for the itinerant harvesters. For the itinerant harvesters, this would be a share in the equivalent of an extra $75 during the harvest period in 1999.17/ Combined with an increase in the share of the total yield of the land worked, the landowners agreement to pay the full amount of the ushr, means that itinerant harvesters working in Musa Qala or Kajaki could receive as much as 7 kg more than they received from a 100 kg yield in Marja. This would constitute an increase in pay of the equivalent of $259, over a 20 day period (see Table 4).

For the individual itinerant harvester, the amount of opium received for their work ranged from 1 kg to almost 3.4 kg for between 13 to 20 days work. Consequently, daily wage rates would appear to fluctuate dramatically, with the lower end of the payments being paid in Marja. For instance, one respondent reported selling the 1 kg of opium he had received for 15 days work in Marja in the local bazaar for the equivalent of $37.00. This equates to a daily wage rate of almost $2.50.

Not surprisingly, the higher payments would seem to have been paid in Musa Qala or Kajaki where the most common payment was approximately one half of one maund, the equivalent of 2.25 kg for 13 to 16 days work.18/ This payment would represent the equivalent of between $5.20 and $6.40 per day. The highest payment reported amongst respondents was in Kajaki where one respondent from Oruzgan claimed that had received the equivalent of 3.4 kg of opium in return for 16 days work, representing a daily wage rate of approximately $7.80.

It is important to note that wage rates for itinerant harvesters in Helmand in 1999 have been higher than in previous years where one sixth or one fifth of the final yield was more common. Consequently, the daily wage rates at the higher end of the scale are considered unusual. However, based on these figures, those itinerant harvesters working in only one district for 16 days, could earn between $40 and $125, whilst those itinerant harvesters willing to work in three districts, with each harvest not exceeding 16 days, could earn from $120 to $374. The final amount earned would of course be subject to the nature of the agreement over the share of the final yield to be paid to the itinerant harvester and the market price of opium at the point of sale.

Moreover, this income could be supplemented with bonus payments from the landowner. Although reports of baksheesh payments were not common amongst respondents, a number of those interviewed did indicate that they had obtained a bonus payment from the landowner when there had been a particularly good yield. This baksheesh was typically paid in opium and could be from 300 to 500 grams of opium.

Given the working conditions, regular food and tea were considered a standard part of the payment for itinerant harvesters. Typically harvesters were found to be working long hours in the hot sun, from sunrise until 10:00 a.m. and then from 2:00 p.m. until dusk. Some respondents who were not experienced in lancing complained of feeling ill, blaming it on the odour of the opium. All respondents reported that three good quality meals were provided by the landowner. Respondents reported that breakfast, which would be served early, was typically bread and tea. Lunch was typically potato or rice, with curry, beans, okra, yogurt and bread, whilst dinner consisted of mutton or beef with vegetables, yogurt and bread. Tea was also provided three or four times during the working day.

Respondents also reported that transportation was sometimes provided for itinerant harvesters as part of their overall payment. Indeed, the landowner was typically found to provide transport for those respondents recruited at the district bazaar. Moreover, key informants revealed that the fear of a labour shortage in Musa Qala and Kajaki prompted some landowners to travel to other districts in search of itinerant harvesters, offering them transport to their next place of work once they had finished their harvesting in that area.

Accommodation was also provided for the itinerant harvesters generally in the landowners guest house, known as the hujera. However, some respondents were interviewed whilst staying in tents near the opium poppy fields that they were harvesting.

�

17/ At the time of field work one kilogramme of opium cost the equivalent of $37 in Helmand.

18/ One Qandahari maund is the equivalent of 4.5 kg.

| 11. Selling the proceeds of their labour Typically, respondents sold the opium they were given as payment in the local area. Indeed, 40% of total sales were made in the bazaar in which the opium had been harvested. The highest incidence of such sales was in Marja where 60% of respondents sold their opium in the district bazaar. A further 30% were found to sell their opium in the nearby bazaar of Lashkargah, in Bust district, and the remaining respondents in Sangin bazaar, Sarban Qala. Both these latter two bazaars are on the route to the opium cultivating districts of Kajaki, Musa Qala and Nawzad. In the districts of Kajaki, Musa Qala and Nawzad, many of the respondents sold their opium either in the local district bazaar or in neighbouring districts depending on their route of travel.

Some of those who cultivated opium poppy on their own land claimed to transport the opium they were paid for their work as itinerant harvesters to their district and combine it with the opium they produced from their own crop. This opium would then be sold at the local bazaar, where respondents believed they could obtain a higher price. The justification of this belief may lie with respondents delaying the sale of their opium until after the local harvest and the subsequent glut in the supply of opium, or the access some respondents may have to better prices due to the patron-client relationships that they have with opium traders in their own area (see Box 4).

| Box 4 The Boy from Marja: A sixteen year old boy from Marja district was interviewed whilst working as an itinerant harvester in Musa Qala. He reported that whilst he had been lancing opium for three years on his father's land, this was the first year in which he had worked as an itinerant harvester. He indicated that his father had 5 hectares of land which had been cultivated with opium poppy and pomegranates. He claimed that his father's share of the final yield from the 4 hectares of opium cultivated was 180 kg of opium, and that the income generated from its sale, would belong to his father. With the encouragement of the itinerant harvesters that were working on his father's land, the boy had decided to travel to Musa Qala to work as an itinerant harvester and generate some income of his own. He predicted that he would be paid approximately 2.25 kg of opium for his work in Musa Qala as well as receive three good quality meals, consisting of meat, vegetables, bread and yoghurt. He indicated that after completing the harvest in Musa Qala he would travel northwards to Baghran to conduct a final harvest, before returning home. He reported that he would sell the opium he earned in Musa Qala and Baghran in Marja district once prices had increased in the post harvest period. He claimed that he would put some of the money he earned towards his engagement.

|

Amongst those itinerant harvesters interviewed, there were two cases of opium use. One respondent was from the refugee camps in Balochistan the other from Nimroz, where key informants suggest opium use has increased dramatically in recent years.

12. Goods purchased with the proceeds of their labour

The vast majority of respondents reported that they would use the income they generated from their work as itinerant harvesters for basic necessities, including wheat, clothes, sugar, and tea. Transportation was also a common response from respondents.

However, given that four of the respondents were students, school fees, books and stationary were also cited as items that would be purchased. Two respondents indicated that they would use the income they earned for the repayment of debts. A further respondent indicated that he would put his payment towards the cost of his engagement.

Only two respondents reported that they would be using the proceeds from their labour for productive investment. The first, from Oruzgan indicated that he would use the income he earned to purchase livestock. Unfortunately, the second respondent reported that he would sell the opium he earned from working as an itinerant harvester in Helmand province in Nimroz, close to the Iranian border, where he reported that he could obtain a higher price. With the proceeds he would purchase more opium in Helmand to sell, once again at the border, and thereby finance his trade in opium.�

13. Findings

Opium is a labour intensive crop and as such, its profitability is vulnerable to increases in the cost of hired labour during harvest time. The cost of itinerant labour for the opium poppy harvest has increased from one sixth to one fifth of the final yield in previous years, to one fifth to one quarter of the final yield in 1999. The extent of opium poppy cultivation in 1999, and the early harvest in Nawzad is thought to have created a local labour shortage, forcing up the cost of labour in Helmand. Combined with the fall in the price of opium, due to the level of opium cultivation and the high yields, this rise in labour costs will have reduced the margin of profit accrued by landowners in Helmand, possibly impacting on their decision to cultivate opium in the 1999/2000 growing season.

Itinerant harvesters in Helmand tend to come from a wide range of areas within Afghanistan and from refugee camps from across the border in south west Pakistan. In total 10 provinces in Afghanistan were represented amongst those interviewed, including provinces in north, south and central Afghanistan. A number of Afghan refugees residing in Balochistan were also interviewed whilst they worked as itinerant harvesters. The distances that respondents were willing to travel to obtain work as itinerant harvesters would tend to suggest that the opium poppy harvest in Helmand provides an important source of seasonal off-farm income for households both within and outside the province.

The majority of itinerant harvesters interviewed were found to come from the provinces of Ghor and Helmand. Within Helmand most of the major opium poppy producing districts were represented by respondents, many of whom reported cultivating opium on their own land. The majority of respondents from Ghor came from those districts in close proximity to Helmand province, including Pasaband, Sharaq and Taiwara. A number of the respondents from Ghor reported that they not only worked in Helmand during the opium poppy harvest but during the poppy weeding season as well, supporting the view that off-farm income opportunities in Ghor are limited and seasonal migration is an important source of livelihood for many of the province's inhabitants.

The majority of itinerant harvesters interviewed worked as itinerant harvesters during periods of agricultural underemployment on their own land. Indeed, the majority of the itinerant harvesters interviewed owned land, particularly those from Ghor and Helmand where the incidence of land ownership was found to be highest. The great majority of respondents from Helmand were found to cultivate opium in their own districts and, during periods when there were few agricultural demands from their own land, work as itinerant harvesters in other districts within the province. Similarly, landownership was high amongst respondents from Ghor, who reported that after completing the opium poppy harvest in Helmand, they would return to their own land to harvest their rainfed wheat. However, landholdings were reported to be small amongst both groups and considered insufficient to satisfy household basic needs.

Itinerant harvesters in Helmand are typically young and male. Those interviewed ranged from 10 years of age to 55. Whilst the average age of the itinerant harvesters interviewed was 24, almost half of those interviewed were under 20 and only 16% of respondents were 35 years or older. Three quarters of respondents reported that they had been working as itinerant harvesters for less than 5 years, whilst one fifth reported that they were harvesting opium poppy for the first time.

Whilst women were not found to work as itinerant harvesters in Helmand province, the opium poppy harvest is a time in which the reproductive and productive roles of women increase dramatically. During the period of employment the landowner is expected to provide three good quality meals and tea by itinerant harvesters. The family members of the landowner, including boys as young as 10, who are working on the harvest, also require regular food and drink due to the arduous nature of the task. The burden of food preparation is carried by the females of the landowners family, who due to the labour intensive nature of the opium poppy harvest and a tradition of exclusion, receive little assistance from the male members of the family.

Most respondents reported that they had learnt how to harvest opium poppy from either their relatives or friends. For those who came from opium producing districts, their first experience of harvesting opium poppy was in their own district and generally on their own land under the tuition of their relatives. Those respondents that did not come from opium producing districts typically conducted their first harvest in Helmand. Those respondents travelling in a group of itinerant harvesters, with no prior experience of lancing and collection of opium were given training by those members who had previously worked as itinerant harvesters in the area.

Recruitment as an itinerant harvester in Helmand would appear to be based on local supply and demand factors rather than traditional family or tribal links. Indeed, few respondents reported that they worked for the same landowner each year. The variance in the time of the harvest of opium poppy each year and the demands of respondents own agricultural land, would seem to mitigate against such habitual arrangements. As such, recruitment would seem to be a function of the time of the opium poppy harvest in the district, the availability of itinerant harvesters, and the result of negotiations between landowner and itinerant harvesters.

Itinerant harvesters are typically mobile, taking advantage of the staggered nature of the opium poppy harvest in Helmand province to increase their off-farm income opportunities. Indeed, only 10% of respondents reported that they harvested opium in one district. Almost two thirds of respondent were found to harvest in two districts, whilst one quarter indicated that they harvested in three districts. Respondents typically began the harvest in the southern districts of Helmand and then travelled northwards as the harvest period reached the districts situated at higher altitudes. Generally, the route respondents travelled and the number of harvests they completed was found to depend on their district of origin and the agricultural needs of their own land.

Whilst the income generated from working as an itinerant harvester is considered important, household agricultural production is given priority by those respondents with landholdings. Indeed, almost one third of respondents reported that they would be returning to their own land to harvest opium at some point during their travel between the different opium poppy producing districts. Moreover, 72% of respondents indicated that they would be returning to their own land to tend to their own crops, many foregoing the possibility of working as an itinerant harvester in another opium producing district. This would tend to suggest that the income earned form working as an itinerant harvester is merely an important supplement to household production rather than a substitute for it.

Itinerant harvesters in Helmand were typically paid a share of the final yield in opium for their work during the harvest. This strategy is preferred by landowners who seek to share the risk of crop failure with itinerant harvesters. Indeed, the payment of a share of the final crop was almost uniform amongst respondents, despite itinerant harvesters preference for a fixed payment of opium based on the size of the land and an agreed number of lances. This would suggest that despite the increase in the share of the total yield paid in 1999, itinerant harvesters do not have the market power to dictate the terms and conditions of their work.

Itinerant harvesters in Helmand generally sold the opium that they received in payment for their work in the local bazaar on the completion of each opium poppy harvest. Whilst respondents who were cultivating opium on their own land tended to combine the opium they were paid with the opium they produced and sell it later in their district of residence, 40% of those interviewed sold the opium they were paid, promptly in the local bazaar in the district in which it was harvested. Few respondents reported storing their opium for any period of time despite the increase in opium prices that are experienced in the post harvest period. This would tend to suggest that the income generated from their work as itinerant harvesters is used to satisfy more immediate needs.

For the majority of respondents, the income obtained from working as an itinerant harvester was used to purchase basic necessities. Wheat, clothes, sugar and tea were the most frequently cited goods to be purchased by respondents with the proceeds of their work as itinerant harvesters. Few respondents were found to be investing the income generated for productive purposes and none reported that they would be purchasing luxury consumer items. This would tend to suggest that the income derived from working as an itinerant harvester is an important contribution to household livelihood strategies.

A failure to provide alternative off-farm and non- farm income opportunities for itinerant harvesters may well result in opium poppy cultivation relocating to new areas, the so called ?balloon effect'. Fieldwork in both the south and east suggests that itinerant harvesters are a major contributory factor in the introduction of opium poppy into new districts in Afghanistan. Small landholdings, increasing demographic pressure and the shortage of off-farm and non-farm income opportunities, limits the livelihood strategies of the resource-poor. The labour intensive nature of opium poppy provides those with insufficient land to satisfy household basic needs with an important source of wage labour. Given that the environmental conditions in many parts of Afghanistan are suitable for opium poppy cultivation, a failure to address the needs of this semi-skilled labour force may increase their vulnerability and prompt their migration to new areas in search of off-farm income opportunities. Fieldwork suggests that itinerant harvesters are currently finding the off-farm income opportunities that they require through the introduction of opium poppy into new areas and facilitating the increase in the intensity of opium cultivation in existing areas of production. This problem needs to be addressed if sustainable and net reductions are to be achieved by regional development interventions aimed at reducing opium poppy cultivation in Helmand province.

14. Recommendations

If both conventional development objectives and alternative development objectives are to be achieved, development interventions aimed at reducing opium cultivation need to target both those who own the land and those who work the land on a short term basis.

Given the increasing fragmentation of landholdings in rural Afghanistan and growing demographic pressures, the development community in Afghanistan needs to give priority to developing labour intensive methods of implementation that provide off-farm and non-farm income opportunities.

Reconstruction and rehabilitation projects, including bridge building, canal cleaning and road repairs, should seek to maximise labour inputs and minimise the use of capital. This strategy would prove more appropriate to the immediate needs of the Afghan community and have possible implications for the availability of hired labour for the opium poppy harvest.

Where possible labour intensive activities should be conducted over an extended period, prior to, during, and after, the opium harvest each year, so as to provide alternative sources of income for itinerant harvesters. Moreover, a coordinated and focused approach by the development community in Afghanistan has the potential to create local labour shortages and raise the labour costs of opium cultivation. This would possibly serve to change households' expectations of future hired labour costs, and combined with other well-targeted development interventions, serve to reduce opium poppy cultivation in subsequent years.

ANNEX A: TERMS OF REFERENCE

Study 4: Access to Labour: The Role of Opium in the Livelihood Strategies of Itinerant Harvesters Working in Helmand Province, Afghanistan

Objective: To further UNDCP's understanding of the source and mobility of the labour force required to harvest opium poppy in Helmand Province, and identify possible strategies to ensure that regional development initiatives aimed at achieving a sustainable reduction in opium cultivation, address the role opium plays in the livelihood strategies of both landowners and labourers.

Summary: This Study will consist of a series of a semi-structured interviews with itinerant labourers harvesting opium poppy in the districts of Marja, Nad-e-Ali, Nahr-e-Saraj, Musa Qala and Nawzad. It will seek to identify the source of the labour for opium poppy in these districts and explore the role of opium poppy cultivation in the livelihood strategies of itinerant harvesters.

The final report will draw together past and current work that has been conducted by C27 on the dynamics of the labour market, including the Baseline Survey and current fieldwork assessing the amount of labour required for poppy cultivation and the role of women and children in opium poppy cultivation. This work will provide a diagnostic for ?Strategic Study 5: The Role of Women in Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan and the Consequences Arising from its Replacement for Women's Economic and Social Standing'.

Methodology: Due to the sensitive nature of the subject emphasis should be on informal interviews. A questionnaire should not be used. Instead the interviewer should focus on a number of key issues discussed in a conversational manner. Notes should not be taken during the interview but should be written up once the interview has finished and the interviewer has departed. Any issues that are not addressed in the TORs but are raised in the interview by the respondent should also be documented.

Emphasis should be given to conducting in-depth interviews over a wide geographical area to assist in identifying generic issues that could be explored in other districts during subsequent stages of the study.

A minimum of fifteen interviews should be undertaken in each district. It is essential that these interviews are conducted over a wide geographical area. Notes for each interview should be written up and forwarded to the Drug Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist combined with a two-page overview for each district. Debriefing will take place after each period of fieldwork.

Time of fieldwork: The Community Mobiliser will need to identify the timing of the harvest and undertake the fieldwork accordingly. However, given the different times of the harvest in the districts the fieldwork should be split into two missions. The first mission will cover the fieldwork for Marja and Nad-e-Ali, the second mission Musa Qala, Kajaki and Nawzad.

KEY ISSUES TO BE DISCUSSED

Origin

1. What is their tribe?

2. What is their sub tribe?

3. From what village and district are they from?

4. Do they have land in their village? How much?

5. What winter crops do they grow?

Motivation

6. Why do they travel to this area to work?

7. What types of work do they do in the area?

8. Are they working in this area for the whole year or just for a short period of time?

9. Are they a sharecropper or day labourer?

Duration

10. In which year did they first harvest opium poppy?

11. Have they harvested opium poppy every year since then?

12. If not, why not?

13. What age were they when they first harvested opium poppy?

Mobility

14. What districts have they harvested opium in over their life time?

15. Do they harvest in the same villages each year?

16. Which districts did they harvest opium poppy 1998?

17. How do they select which villages they will work in each year? Tribal affiliation? Family links?

18. How do they know when the harvest will start in the village that they are working?

19. After completing the harvest in this village what will they do next?

20. If harvest opium, which village or district?

21. When will you return to your village of origin?

Payment

22. How much are they paid for harvesting?

23. Are they paid cash or in-kind?

24. If they are paid in-kind where do they sell the opium?

25. What do they purchase with the money they earn from the opium harvest?

MAP

|

Illustrative Diagram of the Seasonal Migration of Itinerant Harvesters Working in Helmand Province, Afghanistan(Click on picture to enlarge) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Strategic Studies Series One of UNDCP?s principal objectives is to strengthen international action against illicit drug production. In Afghanistan, its principal objective is to reduce and eventually eliminate existing and potential sources of opium cultivation. It is recognised that in order to achieve this there is a need to further the understanding of the diversity of conditions and priorities that different socio-economic and spatial groups take into account when making decisions about their involvement in opium poppy cultivation.

The Strategic Study Series is one of the tools by which UNDCP intends to document the process of lesson learning within the ongoing Afghanistan Programme. Studies in this series will focus on issues that are considered to be of strategic importance to improving the design of current and future alternative development initiatives in Afghanistan. Information collection for these studies is undertaken by the UNDCP Drug Control Monitoring System (AFG/C27) in close coordination with the ongoing presence and project activities of UNDCP?s Poppy Crop Reduction project (AFG/C28). Recognising the inherent problems associated with undertaking research into the drugs issue in Afghanistan, emphasis is given to verifying findings through systematic information-gathering techniques and methodological pluralism. As such, the Studies will be undertaken in an iterative manner, seeking to consolidate preliminary findings with further fieldwork. It is envisaged that this approach will allow panel or longitudinal studies to be undertaken which assess both the changes in opium poppy cultivation and lives and livelihoods amongst different socio-economic, gender and spatial groups over the lifetime of the Afghanistan programme.

These Strategic Studies will be an integral part of the regional study, ?The Dynamics of the Illicit Opiate Industry in South West Asia? due to be published and disseminated in early 2001. The purpose of this regional study will be to: (i) contextualise the illicit drugs situation in South West Asia for the donor community, addressing issues of interest to their development agendas, including poverty, health, gender and the environment (ii) and for UNDCP to identify ?best practice? in the design and implementation of alternative development, law enforcement and demand reduction initiatives.

Strategic Studies will include:

- An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation to New Districts in Afghanistan.

- The Dynamics of Farmgate Opium Trade and the Coping Strategies of Opium Traders.

- The Role of Opium as a Source of Informal Credit.

- The Role of Opium as a Livelihood Strategy for Returnees.

- Access to Labour: The Dynamics of the Labour Market for Opium Poppy in Afghanistan.

- The Role of Women in Opium Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan and the Consequences Arising from its Replacement for Women?s Economic and Social Standing.

- ?The Balloon Effect?: An Analysis of the Process of Relocation of Opium Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan.

Executive Summary

Introduction

Opium poppy is a labour intensive crop. Indeed, estimates suggest that approximately 350 person days are required to cultivate one hectare of opium poppy in Afghanistan, compared to approximately 41 person days per hectare for wheat and 135 person days per hectare for black cumin. Harvesting alone is reported to require as much as 200 person days per hectare.1/ Consequently, to spread the demand on both hired and family labour during the harvest period, households have been found to both cultivate different varieties of opium poppy with differing maturation periods, and stagger the planting of opium poppy.2/However, despite these efforts the majority of opium producing households still require hired labour during the opium poppy harvest.

The varying climatic zones within each of the opium poppy cultivating regions of Afghanistan means that the opium poppy harvest is often staggered, reaching different areas at slightly different times. Consequently, for those who are willing, and able to travel during the harvest season, opium poppy provides a valuable source of off-farm income.3/ As such, opium poppy provides an important source of livelihood not only for those who own the land, but for those that are employed to work the land on a short term basis. This Study seeks to explore the motivations and circumstances that influence individuals in their decision to work as itinerant harvesters and the role that this off-farm income opportunity plays in their overall livelihood strategies.

Methodology

The fieldwork for this Study was undertaken during the harvest of opium poppy in Helmand province in 1999. A total of 75 in-depth interviews were conducted in five districts between 25 April and 18 May 1999. To explore the diversity of both upper and lower Helmand, fifteen interviews were conducted in each of the target districts of Marja,4/ Nad-e-Ali, Musa Qala, Kajaki and Nawzad. Interviews were conducted over a wide geographical area so as to verify findings and distinguish between generic patterns and localised issues.

It is important to note that it is difficult to determine how representative the findings of thisStudy might be. Given the sensitive nature of the fieldwork, respondents were selected based on existing contacts within each of the districts visited. Moreover, the reports of increased opium poppy cultivation in province in 1999 and the rise in payments for those employed as itinerant harvesters, may have led to an influx of new labour to the province. Consequently, the findings of this Study should be taken as indicative, documenting the process by which a cross section of respondents have begun their work as itinerant opium poppy harvesters and the role that this work plays in their overall livelihood strategies.

Findings

The findings of this Study suggest that itinerant harvesters working in Helmand province are typically young, male and can come from a wide range of areas within Afghanistan and from refugees camps in Balochistan. However, the majority of those interviewed for this Studycame from the provinces of Ghor and Helmand. Most of the itinerant harvesters from these two provinces reported that they had landholdings and worked as itinerant harvesters during periods of agricultural underemployment on their own land. All reported that the agricultural production from their landholdings were insufficient to meet family basic needs.

Fieldwork revealed that itinerant harvesters from Helmand province generally cultivated opium in their own districts of residence and travelled between the different climatic zones within the province, taking advantage of the staggered nature of the opium poppy harvest to maximise on and on-farm and off-farm income opportunities. Amongst the respondents from Ghor province, landownership was found to be high, with the majority reporting that after completing the opium poppy harvest in Helmand, they would return to their own land to harvest their rainfed wheat. However, the Study found that respondents from Ghor not only worked in Helmand during the opium poppy harvest but during the poppy weeding season as well, supporting the view that off-farm and non-farm income opportunities in Ghor province are limited and seasonal migration is an important source of livelihood for many of the province?s inhabitants.

Through fieldwork it was discovered that most of the itinerant harvesters working in Helmand province had generally learnt how to harvest opium from either relatives or friends. For those who came from opium producing districts, their first experience of harvesting opium poppy was in their own district and generally on their own land under the tuition of their relatives. Those respondents travelling in a group of itinerant harvesters, with no prior experience of lancing and collection of opium, were given training by those members who had previously worked as itinerant harvesters in the area.

Notably, the Study revealed that finding employment as an itinerant harvester was based on local supply and demand factors rather than traditional family or tribal links. Indeed, few respondents reported that they worked for the same landowner each year. The variance in the time of the harvest of opium poppy each year and the demands of respondent?s own agricultural land, would seem to mitigate against such habitual arrangements. As such, recruitment would seem to be a function of the time of the opium poppy harvest in the district, the availability of itinerant harvesters, and the result of negotiations between landowner and itinerant harvesters.

The Study found that itinerant harvesters typically began the harvest in the southern districts of Helmand and then travelled northwards as the harvest period reached the districts situated at higher altitudes. Generally, the route respondents travelled and the number of harvests they completed was found to depend on their district of origin and the agricultural needs of their own land. The Study found that the majority of respondents were found to harvest opium in two districts, although almost one quarter of those interviewed reported that they harvested in three.

The Study suggests that the payment for working as an itinerant harvester was typically in-kind, with itinerant harvesters receiving one fifth or one quarter of the final yield of the land worked. This method of payment was almost uniform despite itinerant harvesters preference for a fixed payment of opium based on the size of the land and an agreed number of lances. The Study suggests that the landowners preference for sharing the risk of crop failure through paying a share of the final yield, prevailed in Helmand province despite a shortage of labour for the opium poppy harvest in 1999. However, fieldwork revealed that during the height of the labour shortage in Helmand province in 1999, itinerant harvesters managed to use their market power to negotiate improved arrangements for the payment of the local agricultural tax known as ushr.

It is interesting to note that whilst the income generated from working as an itinerant harvester was considered important to the household livelihood strategies of itinerant harvesters, agricultural production on their own land was given priority. Indeed, the Studyreveals that almost three quarters of respondents would be returning to their own land to tend to their crops, many foregoing the possibility of working as an itinerant harvester in another opium producing district.

The Study found that most of those interviewed sold the opium they were paid in the local bazaar once they had completed each harvest. Few respondents reported storing their opium for any period of time despite the increase in opium prices that are experienced in the post harvest period, suggesting that the income generated from their work as itinerant harvesters is used to satisfy more immediate needs. Moreover, the Study suggests that the majority of itinerant harvesters, used the income they earned from the opium harvest for purchasing basic necessities including wheat, clothes, sugar and tea and that few respondents were found to be investing the income generated for productive purposes. This would tend to suggest that the income derived from working as an itinerant harvester is an important contribution to household livelihood strategies.

Whilst women were not found to be working as itinerant harvesters or even lancing or collecting opium on household land, the Study did manage to explore the role of women during this labour intensive period. It was found that the workload of women was found to increase significantly due to the burden of food preparation for both household and hired labour. Moreover, the emphasis on maximising the use of male household labour meant that little assistance was provided by other family members for household tasks, further increasing the reproductive role of women.

Conclusion

The Study suggest that labour intensive nature of opium means that its profitability is vulnerable to increases in the cost of hired labour during harvest time. As such, the Studyconcludes that greater consideration needs to be given to both those who own land and those who work land on a short term basis. Indeed, given the increasing fragmentation of landholdings in rural Afghanistan and the absence of non-farm income opportunities, there would appear to be a need to address the needs of itinerant harvesters during the design and implementation of regional development initiatives aimed at achieving a sustainable reduction in opium cultivation. A failure to provide alternative off-farm and non-farm income opportunities for these mobile workers may well result in opium poppy cultivation relocating to new areas, the so called ?balloon effect?. Fieldwork in both the eastern and southern regions has already revealed that itinerant harvesters play an important role in the expansion of opium poppy cultivation into new districts in Afghanistan.5/ Consequently, to neglect the needs of this group would appear to be to the detriment of both alternative development and conventional development objectives.

Recommendations

So as to address both alternative and conventional development objectives the Studyrecommends that the development community gives increasing priority to improving off-farm and non-farm income opportunities in Afghanistan. Particular attention needs to be given to developing labour intensive methods of implementation that provide off-farm and non-farm income opportunities. For instance reconstruction and rehabilitation projects, including bridge building, canal cleaning and road repairs, should seek to maximise labour inputs and minimise the use of capital. This strategy would prove more appropriate to the immediate needs of the Afghan community and have possible implications for the availability of hired labour for the opium poppy harvest.

Moreover, where possible labour intensive activities should be conducted over an extended period, prior to, during, and after, the opium harvest each year, so as to provide alternative sources of income for itinerant harvesters. A coordinated and focused approach by the development community in Afghanistan may have the potential to create local labour shortages and raise the labour costs of opium cultivation. This would possibly serve to change households? expectations of future hired labour costs, and combined with other well-targeted development interventions, serve to reduce opium poppy cultivation in subsequent years.

However, the Study recommends that close monitoring will be required to assess the cost-effectiveness of such an approach. Household response strategies to an increase in wage labour opportunities during this time may include the increased use of family labour for the opium poppy harvest, including women, children and the elderly. If both conventional and alternative development objectives are to be achieved, it is important that the burden on these vulnerable groups are not increased.

�

1/ See Socio-Economic Baseline Survey for UNDCP Target Districts in Afghanistan(forthcoming).

2/ See the Afghanistan Annual Opium Poppy 1999 (forthcoming) and Strategic Study 1: An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation into New Districts in Afghanistan (Preliminary Report, July 1998).

3/ 'Off-farm income typically refers to wage or exchange labour on other farms (i.e. within agriculture) ......... [whilst] non-farm income opportunity refers to non-agricultural income sources.' See Ellis (1998) 'Livelihood Diversification and Sustainable Livelihoods' in Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: What Contribution can we make? DFID: London.

4/ Due to local views and the consensus of respondents, this report refers to the 'district' of Marja, which is part of the command area of the Boghra canal and within Nad-e-Ali district. It lies south of the town of Nad-e-Ali itself and directly west of the district of Nawa Barakzai.

5/ See Strategic Study 1: An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation into New Districts in Afghanistan (Preliminary Report, July 1998).

| 1. Objective To further UNDCP?s understanding of the source and mobility of the labour force required to harvest opium poppy in Helmand Province, and identify possible strategies to ensure that regional development initiatives aimed at achieving a sustainable reduction in opium cultivation, address the role opium plays in the livelihood strategies of both landowners and labourers.

2. Introduction

Opium poppy is a labour intensive crop. Indeed, estimates suggest that approximately 350 person days are required to cultivate one hectare of opium poppy in Afghanistan.6/ These estimates would appear to be consistent with other source areas such as Thailand and Laos where estimates of the labour required for the cultivation of opium poppy range from 300 to 486 person days per hectare.7/