The Strategic Studies Series

One of UNDCP's principal objectives is to strengthen international action against illicit drug production. In Afghanistan, its principal objective is to reduce and eventually eliminate existing and potential sources of opium cultivation. It is recognised that in order to achieve this there is a need to further the understanding of the diversity of conditions and priorities that different socio-economic and spatial groups take into account when making decisions about their involvement in opium cultivation.

The Strategic Study Series is one of the tools by which UNDCP intends to document the process of lesson learning within the ongoing Afghanistan Programme. Studies in this series will focus on issues that are considered to be of strategic importance to improving the design of current and future alternative development initiatives in Afghanistan. Information collection for these studies is undertaken by the UNDCP Drug Control Monitoring System (AFG/C27) in close coordination with the ongoing presence and project activities of UNDCP's Poppy Reduction project (AFG/C28). Recognising the inherent problems associated with undertaking research into the drugs issue in Afghanistan, emphasis is given to verifying findings through systematic information-gathering techniques and methodological pluralism. As such, the Studies will be undertaken in an iterative manner, seeking to consolidate preliminary findings with further fieldwork. It is envisaged that this approach will allow panel or longitudinal studies to be undertaken which assess both the changes in opium cultivation and lives and livelihoods amongst different socio-economic, gender and spatial groups over the lifetime of the Afghanistan programme.

These Strategic Studies will be an integral part of the regional study, "The Dynamics of the Illicit Opiate Industry in South West Asia" due to be published and disseminated in early 2001. The purpose of this regional study will be to: (i) contextualise the illicit drugs situation in South West Asia for the donor community, addressing issues of interest to their development agendas, including poverty, health, gender and the environment (ii) and for UNDCP to identify ?best practice' in the design and implementation of alternative development, law enforcement and demand reduction initiatives.

Strategic Studies will include:

- An Analysis of the Process of Expansion of Opium Poppy Cultivation to New Districts in Afghanistan.

- The Dynamics of Farmgate Opium Trade and the Coping Strategies of Opium Traders.

- The Role of Opium as a Source of Informal Credit.

- The Role of Opium as a Livelihood Strategy for Returnees.

- Access to Labour: The dynamics of the labour market for opium poppy in Afghanistan.

- The Role of Women in Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan and the Consequences Arising from its Replacement for Women's Economic and Social Standing.

- ?The Balloon Effect': An Analysis of the Process of Relocation of Opium Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan.

Executive Summary

Currently, little is known about the structure of the farmgate trade in illicit drug crops. It is apparent from work in other drug crop producing areas that prices for coca and opium can be quite localised. However, it is unclear what influence traders have in determining the farmgate price of illicit crops and, consequently, the relative profitability of alternative sources of livelihood and the ultimate success of alternative development interventions.

The market power of traders to set opium and coca prices will largely depend on the degree of competition that exists in the illicit drugs trade in the local area at the different levels in the trading chain. Experience would certainly suggest that the illegal nature of the drug trade and associated violence and intimidation, limits the degree of competition at the wholesale level, resulting in a small number of large traders dominating the trade in bulk purchases of drug crops. However, at the level of the farmgate the degree of competition is less well known. Yet, it is at this point in the chain where household decision making over cropping patterns is informed.

This study explores the market structure of the farmgate opium trade, including the degree of competition, barriers to entry, profit margins, credit, the socio-economic profile of sellers, both pre and post-harvest, and the geographic mobility of traders. The strategies traders envisage undertaking in response to UNDCP?s Afghanistan Programme are also examined.

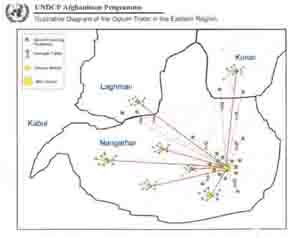

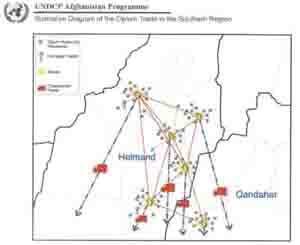

The Study seeks to follow-up on a number of interviews conducted by the Drug Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist in 1997 with opium traders in Khakrez. In total 38 interviews were conducted with opium traders in the provinces of Nangarhar, Qandahar, and Helmand between 14 June and 19 August 1998. Of these 38 interviews, 12 were undertaken in the districts of Shinwar and Achin, Nangarhar province, between 14 and 18 June 1998. To identify possible commonalities and differences between the opium trade in the eastern and southern regions, 26 interviews were conducted in the provinces of Helmand and Qandahar between 9 and 19 August 1998. Eighteen of these interviews were undertaken in Helmand in the districts of Kajaki, Musa Qala, Nowzad, Sarban Qala , with a further 8 interviews in the district of Maiwand in Qandahar. To verify the findings a number of key informants with in-depth knowledge of the opium trade were also interviewed in both the eastern and southern regions.

Interviews were semi-structured, focusing on a number of key issues in a conversational manner. A questionnaire was not used and notes were taken after the interview had been completed and the team had departed from the respondent.

The findings of this fieldwork would suggest that:

The structure of the opium trade differs markedly between the eastern and southern regions. It would certainly appear that the process of centralisation in the east has led to short term price differentials with the lowest farmgate prices occurring in those areas located the furthest distance from the dominant opium market in the eastern region, Ghani Khel. These price differentials appear to have created a class of short term, speculative farmgate traders that during the opium harvest exploit their proximity to Ghani Khel to travel to outlying districts and provinces where the inhabitants are either not fully aware of any increase in the price of opium, or, are unwilling to travel to Ghani Khel due to travel costs rendering the sale of small amounts of opium unprofitable.

The geographic location of Ghani Khel, would appear to be a determining factor in the dominance of Ghani Khel bazaar in the opium trade in the eastern region. Ghani Khel is located centrally, both logistically within the eastern region, and politically within the Shinwari tribe. Indeed, key informants report that prior to the war and Ghani Khel?s dominance, Kahi bazaar in Achin district was the centre of the opium trade in the eastern region. The significance of Kahi was a consequence of its central location in the loya woliswoli, or greater district, of Shinwar, consisting of Deh Bala, Achin, Nazian, Durbaba and Shinwar, all traditional opium growing districts. The regional centre for the greater district of Shinwar was in Ghani Khel, where a significant government presence was maintained. Within the greater Shinwar district, Kahi retained a degree of autonomy from the authorities, allowing the opium trade to exist without interference. With the conflict in Afghanistan and the breakdown in the rule of law and civil administration, the regional centre for the opium trade appears to have shifted to Ghani Khel. Moreover, when viewed within the context of the expansion to the north in the area cultivating opium poppy, it would appear that Ghani Khel is better placed both geographically and logistically than Kahi due to its proximity to the asphalt road.

The influx of large traders to Ghani Khel, purchasing significant amounts of opium for processing within Afghanistan would appear to consolidate the centralisation process in the east. The commission system operating in Ghani Khel also strengthens the bazaars central role in the eastern opium trade, providing the necessary incentive to ensure that those purchasing opium trade and store their opium in Ghani Khel. As such the commission system ensures a steady supply of opium is maintained in Ghani Khel bazaar to meet the demands of large traders.

In the south, the presence of numerous buyers and sellers have led to a more decentralised and ?free? market structure. Opium prices would appear to vary little between districts and provinces. Consequently there is little economic advantage in traveling between regions. The existence of a low mark-up on opium in the southern region is supported by the high incidence of mixing of the different qualities of opium, the addition of adulterants, and the increasing evidence of farmgate traders transporting opium to the southern and eastern borders. All this would tend to suggest that where possible opium traders, like traders in any business are continually pursuing strategies to increase the returns on their trade and offset the losses that they are incurring. Moreover, reports suggest that prior to the war Musa Qala played a central role in the opium trade in the southern region. However, insecurity in the area due to conflict within the mujaheddin movement prompted traders to relocate their operations to Sangin. With improved security and the demise of the factionalism of the commanders, Musa Qala has once gain emerged as an important opium bazaar in the southern region. However, in the south a number of other bazaars have also developed direct links with Baloch traders from both Pakistan and Iran, resulting in a more decentralised market structure.1/

The opium trade in the eastern region shows evidence of vertical integration on the basis of tribe rather than a well organised formal institutional structure. Traditionally the cross border trade has been associated with particular tribal groups that span Afghanistan?s borders with its neighbours in the south and east. In the south, numerous Baloch tribes are reported to be heavily involved in the cross-border trade in opium, whilst Pashtoon tribes have traditionally focused on opium poppy cultivation and the trade within Afghanistan. In the east, Shinwari Pashtoons have not only traditionally cultivated and traded opium but through their links with Afridi Pashtoons on the other side of the border have developed a virtual monopoly on the processing and final transportation of heroin into Pakistan. This tribal dominance is reported to consolidate the importance of Ghani Khel within the opium trade in the eastern region. Whilst the sheer number of Baloch tribes in the cross border trade has facilitated a process of decentralisation, with numerous bazaars emerging as important international markets for opium within the southern region.

The growing incidence of heroin processing within eastern Afghanistan is also reported to have exacerbated the process of centralisation in the eastern region. Respondents and key informants indicate that heroin processing requires access to the ?right people? with either the knowledge of the production process, or the influence to ensure processing and trading could be undertaken without restriction. In the eastern region, it is the Shinwari that have developed these links through their contacts across the borders. In the southern region, processing would appear to be limited, largely restricted to morphine base in the far south and far south east of the country and under the control of Baloch traders. Seizure records from Iran would tend to support the prevalence of the trade in opium in the south. For instance, between 1990 and 1997 there has been a considerable increase in the amounts of opium seized by the Iranian authorities, increasing from 20.8 mt in 1990 to 162.4 mt in 1997. Whilst morphine base has continued to increase from 4.5 mt to 19.0 mt between 1990 and 1997, seizures of heroin have remained relatively stable during the same period at approximately 2 mt per annum.

The opium trade in Afghanistan would appear to be integral to the livelihood strategies of a variety of different stakeholders, not just opium cultivators.Fieldwork suggests that farmgate opium traders, like opium cultivators, are heterogenous, ranging from owner cultivators who use any surplus income they may have to engage in short term, speculative trading during the harvest period, to large scale specialist opium traders who purchase opium throughout the year and adopt a variety of strategies aimed at increasing their profit margins, including providing advance payments, mixing, and transporting dried opium to the border areas.

The proportion of large traders interviewed who had performed Haj, and their claim that they believed the trade in opium to be un-Islamic, would suggest that economic needs and motivations are given priority over religious strictures. Indeed, fieldwork suggests that opium traders often have a number of sources of income but believe these to be insufficient to satisfy their needs and those of their families. Whilst those trading in larger amounts of opium over the full year are found to be relatively wealthier than most Afghans, high household dependency ratios continue to constrain improvement in family living conditions. Moreover, diminishing landholdings and the scarcity of viable legal employment opportunities for family members has created a dependency on the opium trade. Whilst there is an obvious need to develop advocacy initiatives aimed at increasing the social and religious stigma associated with the cultivation and trade in opium, it would appear that these will not be sufficient to influence individuals in their decision to abandon opium as a source of livelihood. Wider economic growth and social and political stability are essential pre-conditions to eliminating opium cultivation and trading in Afghanistan.

The profit derived from the trade in opium does not appear to be substantial in absolute terms. Indeed, in the east the mark-up on the rapid turnover trade, where traders were found to purchase and sell opium quickly to take advantage of local price differentials, was found to range between $3.00 and $9.00 per kg. In the southern region the mark-up on this type of trade was even less at the equivalent of only $1.20 to $3.20 per kg. However, according to respondents the profit margins of the opium trade are attractive in relation to the alternative sources of income currently available in Afghanistan, particularly to individuals who have received an intermediate education.

Whilst there would appear to be opportunities to increase the profit margins significantly through the provision of salaam, all those interviewed had adopted a cautious approach to providing advance payments on opium.Indeed, traders recognised that profits could be significantly increased by providing advance payments, known as salaam, for opium prior to the harvest. In the east, the mark up-on opium bought via salaam was between $21.80 to $55.20 per kg, compared to $41.30 to $49.50 in the southern region. However, the high risk nature of this approach due to crop failure, fluctuating prices, and debtors absconding, led traders to adopt a more cautious approach, where advances are only given to a limited number of ?trusted? individuals.

Whilst individuals would appear to be relatively free to enter the opium trade, constrained only by surplus cash flow, trust would appear to be an important feature of business relationships. The uncertain socio-economic and political environment of Afghanistan combined with the illicit nature of the trade, expose traders to significant risk. Deception regarding the quality of opium and payment of debts, combined with volatile prices and exchange rates have resulted in all traders experiencing losses both during the initial years of trading and throughout their trading careers. Consequently, traders would appear to prefer to trade with those people that they have purchased opium from before. However, whilst working with trusted individuals is preferential, opium traders are willing to travel to new areas and conduct business with strangers if it is profitable enough.

It is important to note that whilst all the traders interviewed associated an economic risk with trading in opium, few perceived any threat of arrest or punishment by the local authorities. Indeed, in the east and south respondents indicated that improvements in the security situation over the last few years had reduced the incidence of robbery and the amount of taxes opium traders traditionally had to pay under the mujahedin. Moreover, in the east, the improved security situation would appear to have led to an expansion in the number of individuals exploiting their privileged geographical position to enter into speculative, short term, opium trading.

Whilst the trade in opium in Afghanistan would appear to be competitive it is on the whole peaceful. Individual opium traders are found to vary prices according to prevailing supply and demand. The small profit margins on the post-harvest trade result in traders seeking to maximise the amount of opium they buy and sell through commissioned trade and cooperative arrangements with other traders. Reports of violence and intimidation in either the eastern or southern region are rare.

It is interesting to note that there are different qualities of opium in Afghanistan. The different quality of opium and its concomitant impact on price would suggest that there may be greater chance of achieving sustainable reductions in opium cultivation in areas irrigated by canals and rivers rather than those irrigated by karez. The reason for this assessment is not purely the availability of water and thereby the potential for the introduction of alternative cropping systems but also the competitiveness of alternative crops compared to the relatively low value of opium produced in these areas.

1/ The Baloch are a tribal group that traditionally occupy south west Pakistan, south east Iran and parts of southern Afghanistan.

1. ObjectiveThis Study seeks to further UNDCP?s understanding of the market structure of the farmgate trade in opium and identify the possible responses of traders to a reduction in the supply of opium.

2. Introduction

Currently, little is known about the structure of the farmgate trade in illicit drug crops. It is apparent from work in other drug crop producing areas that prices for coca and opium can be quite localised. However, it is unclear what influence traders have in determining the farmgate price of illicit crops and, consequently, the relative profitability of alternative sources of livelihood and the ultimate success of alternative development interventions.

The market power of traders to set opium and coca prices will largely depend on the degree of competition that exists in the illicit drugs trade in the local area at the different levels in the trading chain. Experience would certainly suggest that the illegal nature of the drug trade and associated violence and intimidation, limits the degree of competition at the wholesale level, resulting in a small number of large traders dominating the trade in bulk purchases of drug crops. However, at the level of the farmgate the degree of competition is less well known. Yet, it is at this point in the chain where household decision making over cropping patterns is informed.

Where the trade in illicit crops is highly localised and dominated by large traders who directly employ agents to purchase opium and coca at the farmgate, it is possible that short term reductions in the supply of drug crops will be felt immediately. This vertically integrated model allows traders to respond immediately to any short term reduction in drug crop cultivation with a concomitant increase in market prices, hampering efforts at promoting alternative livelihoods.

However, where the farmgate trade in drug crops is relatively free with numerous buyers and sellers operating independently, the market power of larger traders will be more diffuse. Within this model, localised reductions in drug crop cultivation will not necessarily be transmitted to major traders through the price mechanism due to the availability of drug crops within the region. In this model strong patron-client relationships and the threat of violence may restrict large traders from buying opium and coca from other regions despite lower farmgate prices. Consequently, where production continues to fall over a period of time and existing stocks are run down, local shortages will occur and prices may increase substantially despite an abundance of drug crops in neighbouring regions or countries. Within this model alternative development initiatives have a longer time frame in which to influence household decision making before provoking a response in prices that affect the competitiveness of alternative sources of livelihood.

This study explores the market structure of the farmgate opium trade, including the degree of competition, barriers to entry, profit margins, credit, the socio-economic profile of sellers, both pre and post-harvest, and the geographic mobility of traders. The strategies traders envisage undertaking in response to UNDCP?s Afghanistan Programme are also examined.

3. Methodology

This Study seeks to follow-up on a number of interviews conducted by the Drug Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist in 1997 with opium traders in Khakrez. Due to the sensitivities associated with interviewing opium traders and the problems of access, emphasis was given to conducting a limited number of in-depth semi-structured interviews. In order to verify findings and distinguish between generic patterns and localised issues, in-depth interviews were conducted over a wide geographical area.

In total 38 interviews were conducted with opium traders in the provinces of Nangarhar, Qandahar, and Helmand. Of these 38 interviews, fourteen were undertaken in the districts of Shinwar and Achin, Nangarhar province, between 14 and 18 June 1998. Twelve of these interviews were conducted with traders in opium, the other two interviews with recipients of advances from traders. Eleven interviews were held in the Shinwar district and three in Achin district.

To identify possible commonalities and differences between the opium trade in the eastern and southern regions, 26 interviews were conducted in the provinces of Helmand and Qandahar between 9 and 19 August 1998. Eighteen of these interviews were undertaken in Helmand in the districts of Kajaki, Musa Qala, Nowzad, Sarban Qala, with a further eight interviews in the district of Maiwand in Qandahar.

To verify the findings a number of key informants with in-depth knowledge of the opium trade were also interviewed in both the eastern and southern regions.

Interviews were semi-structured, focusing on a number of key issues in a conversational manner. A questionnaire was not used and notes were taken after the interview had been completed and the team had departed from the respondent.

In Shinwar interviews were conducted over a wide geographical area. Interviews in Achin served to further widen the geographical spread and to bypass the security problems associated with interviewing shopkeepers in Ghani Khel bazaar. In the South it was possible to conduct a number of interviews with large traders either in the opium bazaars or in a less public environment.

The degree of trust that UNDCP staff have established with the community in Shinwar proved invaluable in conducting the interviews with farmgate opium traders. Farmgate traders showed a willingness to talk openly about the trade in opium in the area and there was a high degree of consistency in the information provided by each respondent in both Shinwar and Achin. Indeed, the degree of consistency meant that 12 interviews were sufficient for analytical purposes. More interviews would not have provided any ?value added? but may have raised suspicions due to a shortage of gatekeepers for other traders.

As is evident from the response of opium traders in Ghani Khel bazaar there are sensitivities associated with those more heavily involved in the opium/heroin trade in the east. However, in the south these sensitivities were overcome through the close contacts that were established with large opium traders during a preliminary visit to the area. The sheer number of large traders, the decentralised nature of the market, and the mobility of trade between the numerous bazaars in the region, also made the environment more conducive to conducting interviews with individuals who traded in large amounts of opium.

4. A socio-economic profile of opium tradersAll of the farmgate traders interviewed owned land, ranging from one fifth of one hectare to twelve hectares. Moreover, all had other sources of income other than that derived from trading in opium, including agriculture, livestock, transportation, timber, and shopkeeping.

Whilst most of the traders indicated that they had larger than the average landholdings within their particular area, the majority argued that they had insufficient land to satisfy the basic food requirements of their family. A number of respondents in the south indicated that there were more than 30 family members within their household. However, respondents claimed that these large households had particularly high dependency ratios and rarely contained more than 4 or 5 working family members. Indeed, one respondent who claimed to purchase 20 metric tons (mt) of opium per annum, the largest amount of any of those interviewed, shared the equivalent of 6 hectares of land between 30 family members.

Approximately 60% of those interviewed in Shinwar and Achin traded less than 100 kilogrammes (kg) of opium per annum, concentrating their trade around the harvest period in the eastern region. The other respondents traded between 200 kg and 500 kg per annum buying and selling opium throughout the year if their cash flow permitted. However, in the south it was possible to interview opium traders who claimed to purchase and sell significant amounts of opium, ranging from 270 kg to 20 metric tons. Most of these respondents appeared to be influential members of the community, having performed Haj, received a relatively high level of education and possessing large landholdings.

Indeed, over one half of those traders interviewed in the south had been educated up to 16 years of age, whilst a number of respondents in both the east and south were former teachers and government workers. With the breakdown in the civil administration, many respondents in the south argued that there were very few income earning opportunities available to those who had received an intermediate level of education. Many respondents suggested that trading in opium was a natural choice for those who had received an education, whilst cultivating opium was the obvious livelihood strategy for those without a formal education.

The vast majority of those interviewed in Shinwar and Achin were less than 30 years old and claimed to be the first generation of their family to be trading in opium. Only 2 of the 12 respondents from Shinwar and Achin claimed to have been trading for 10 or more years. The other ten respondents reported that they had traded in opium for between 3 to 5 years. In the south, the majority of respondents were over 40 years old and claimed to have been trading in opium for between 4 to 8 years. However, almost 20% of those interviewed in the south, indicated that they had been purchasing opium for between 25-30 years, witnessing a considerable expansion in the number of individuals trading in opium over that time.

In the south, it was particularly noticeable that 22 of the 26 opium traders interviewed had performed Haj. Indeed, two respondents were mullahs, suggesting that economic priorities are given precedence over Islamic strictures.

All of those interviewed in the south owned at least either a car, a motorcycle or a tractor, many had all three. Moreover, half the respondents had married a second wife, and some had married for the third time. It is possible that the prominence and wealth of these traders within their respective communities may influence other members of the community in the choice of livelihood.

5. Raising the initial investment funds to begin opium trading

In both the east and the south those traders who only bought and sold opium during the harvest period typically used the opium cultivated on their own land as a source of funds with which to begin their periodic trading in opium. In Shinwar, the proximity of Ghani Khel allowed these traders to sell direct to the wholesale traders in the bazaar at the time when the price for opium was relatively high. Each year the proceeds from this sale would then be used to purchase opium in outlying districts where the price of opium was less competitive.

Respondents who traded in opium throughout the year tended to raise their initial investment costs through loans from family members and friends, trading in other goods, or from shopkeepers. For instance in Shinwar, a respondent reported taking an initial loan of the equivalent of $543 from a shopkeeper in Ghani Khel to begin trading in opium.2/ After ten years of trading in opium he estimated that his investment funds for purchasing opium during the 1997/98 season were almost $3,300.

In the south respondents and key informants indicated that advances for initial investment in the opium trade were obtained through a commission system that operates at all levels of the opium trade in the southern region.3/ For instance, in Musa Qala one trader claimed that his initial investment in the opium trade was made in 1994 and was the equivalent of approximately $270. This was obtained from a Baloch trader as an advance for the purchase of opium. By 1998 he claimed that he had almost $9,000 available for the purchase of opium.

A minority of those interviewed in the south also traded in other goods, such as groceries and fertiliser. These traders had used the profits from this trade to finance their move into the opium trade. This was also the experience in Achin, where all three of the traders interviewed used their trade in general goods and cloth to subsidise their diversification into the opium trade. Other traders reported selling luxury items to raise the necessary finances to begin trading in opium.

2/ At the time of fieldwork in the eastern region there were 46 Pakistan Rupees to one US Dollar, whilst at the time fieldwork was conducted in the south, there were 56 Pakistan Rupees to one dollar and 625 Afghanis to one Pakistan Rupee.

3/ See Section 9.

6. The structure and profitability of the farmgate opium tradeThere was an overwhelming consensus amongst respondents that a shortage of adequate alternative income earning opportunities and increasing demographic pressures had compelled them to begin trading in opium. There was also a general agreement in both the eastern and southern regions that currently trading in opium offered higher profit margins than trading in other commodities such as livestock or agricultural goods. However, fieldwork also revealed significant differences between the structure of the opium trade in the eastern and southern regions that may assist in furthering our understanding of the process of centralisation that has occurred in the illicit drug trade in other countries.

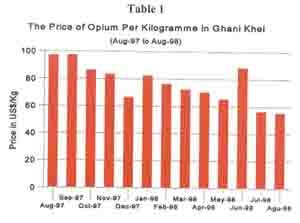

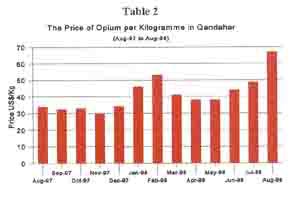

Indeed, data on prices collected over the previous 12 months would tend to support the claim that there are distinct market structures in the eastern and southern region (see Table 1 and 2). Whilst it is recognised that there is a need to use a longer time series to be more conclusive, the trends in opium prices over the last 12 months tend to follow the pattern of a typical annual agricultural crop with opium prices reaching their lowest price during the harvest period and rising during those months following and preceding the harvest period. However, in the east prices do not seem to follow the same trend, fluctuating widely with no distinguishable pattern. It is possible that the absence of a trend similar to that experienced in the south may be a consequence of the process of centralisation that dominates the opium trade in the eastern region.

6.1. Centralisation in the east

All the farmgate traders interviewed in Shinwar indicated that they did not tend to buy opium from households within the district. It was suggested by respondents that the proximity of the inhabitants of Shinwar district to Ghani Khel meant that opium producing households were fully aware of the current price of opium and faced few logistical constraints in transporting their opium to the market. Consequently, most opium producing households sold their crop directly to any one of approximately forty shopkeepers in Ghani Khel bazaar who specialise in the buying and selling of opium.

The great majority of respondents in Shinwar indicated that the focus of their trade was in the outlying districts of Mohmand Dara, Khogiani and Rodat. The provinces of Kunar and Laghman were also popular locations for buying opium for farmgate traders from Shinwar district. The rationale for trading in these outlying districts and provinces was that prices were lower than in Ghani Khel.

Respondents indicated that their proximity to Ghani Khel gave them a distinct advantage over opium producing households and traders in the outlying districts and provinces. All respondents in both Shinwar and Achin and key informants indicated that Ghani Khel is the centre of opium trading in eastern Afghanistan. Consequently, major traders often visit the bazaar to purchase large quantities of opium for processing into morphine base or heroin. These purchases can consist of as much as ten metric tons of opium during one visit, resulting in local shortages in the bazaar and substantial increases in the price of opium.

Respondents and key informants indicated that the price of opium in Ghani Khel bazaar was determined by the demand for opium from these large traders, suggesting that when the processing and smuggling of opium and its derivatives is constrained by law enforcement activities there was a corresponding fall in the price of opium in Ghani Khel bazaar.

Farmgate opium traders in Shinwar reported that the fluctuating price in opium acts as an incentive for them to travel to outlying areas where the inhabitants are, either not fully aware of any increase in the price of opium in Ghani Khel bazaar, or, are unwilling to travel to Ghani Khel due to travel costs rendering the sale of small amounts of opium unprofitable. In Achin farmgate traders reported that they purchased opium in the more remote areas of the district for precisely the same reasons, selling the opium in either Ghani Khel or Kahi, the district centre, and formerly the centre of opium trading in eastern Afghanistan.

All the respondents indicated that there were no restrictions on their mobility and they could purchase opium from any individual in any village or district without fear of intimidation or threats from other traders, or the local authorities. Price and quality were the only determining factors when purchasing opium. For instance, one trader reported purchasing a total of 8 seer or 10 kg of opium from five different farmers in Lagliman for $34.40 per kg in mid-June. Each kg was sold the next day for $43.20 in Ghani Khel bazaar. The trader estimated that the costs he incurred were purely transport related and amounted to approximately $3.00. Indeed, the majority of respondents indicated that the mark-up on this type of rapid-turnover trade were between $3.00 to $9.00 per kg.

Respondents recognised that opium prices reach their highest during the period from October until April when there is a shortage of opium to be sold. Prices during this period can rise to over twice the level of the previous harvest price. The majority of respondents recognised that they should hold onto their opium and trade later in the year when prices were at their highest. However, few reported that they retained their opium for long periods of time as they were compelled to sell quickly due to cash flow problems.

Whilst Ghani Khel represents the regional centre of opium trading in eastern Afghanistan, key informants and respondents reported that there are also a number of district bazaars that operate as centres for a more localised trade. In Achin it was possible to interview a number of shopkeepers that traded opium from their general stores.

These shopkeepers indicated that they operated with very low overheads with both buyers and sellers trading opium with them on the shop premises. Whilst respondents indicated that in the rural bazaars in Achin shopkeepers colluded to fix the price of opium, advances were unique, arranged between the shopkeeper and individual household. One shopkeeper reported providing the equivalent of $3,260 in advances during the period from October until April 1997/98.

The shopkeepers interviewed indicated that they were not representatives of the larger traders operating out of Ghani Khel bazaar but acted independently. However, they did report that they had ongoing business relationships with specific traders in Ghani Khel. These relationships tended to have developed over a number of years and involved bulk purchases and the provision of loans to begin trading. For instance, one shopkeeper claimed under such an arrangement, a trader in Ghani Khel bazaar, who had provided the initial funds for him to diversify into opium trading, traveled to Achin each month to purchase opium from him in 60 kg loads. The maximum amount of opium this intermediary trader reported selling to Ghani Khel on any one occasion was 125 kg.

Key informants report that the dominant market position that Ghani Khel has secured within the opium trade in the east has led to many of the bazaars in the regions acting as tributaries, channeling local purchases of opium to Ghani Khel. Consequently, it is argued by key informants that the type of patron-client relationship that exists between large traders in Ghani Khel and smaller traders in Achin is not atypical for the region.

6.2. Decentralisation in the south

Interviews in the south revealed that, as opposed to the eastern region, opium prices vary very little from district to district. Typically the faringate price across the southern region for the highest quality opium ranged from $60.30 to $62.20 per kilogram, whilst the poorest quality, opium, was being bought at the faringate for the equivalent of $44.00 per kg. The best quality dry opium was being bought for $82.50 per kg, almost twice that of Ghani Khel.

The relatively high price of opium in the south was explained in terms of both significant reductions in the yield of opium poppy in the southern region in 1998 and the opening of the northern borders to trade, following the taliban's recent victories. Indeed, prior to fieldwork opium prices increased dramatically in the south from $32.00 per kg in May to between $60.20 and $63.20 per kg in August, twice that of the August price in 1997. However, as opposed to the mark-up reported in the east, the majority of traders interviewed in the south suggested that they earned only $1.20 to $3.20 per kg on the buying and selling of wet opium post-harvest.

Although respondents in the south were willing to travel further afield if prices were found to be particularly low, the nominal difference in the price of opium between areas resulted in a largely localised trade. Indeed the bulk of faringate purchases were in the district in which respondents lived or those neighbouring it. Further purchases required to satisfy bulk orders by cross-border traders were made at any one the numerous bazaars in the southern region. During the fieldwork it was possible to witness the mobility of trade between the numerous bazaars in the region through discussions with visiting traders.

Indeed, interviews revealed that in the southern region there are a number of bazaars where opium is purchased directly by traders from Pakistan, Iran and, less so frequently, the Central Asian Republics. Each of these bazaars has a number of shops which specialise in opium trading. However, during the harvest season it was reported that most of the shops trading in other goods diversify into small-scale opium trading.

Respondents indicated that Sangin had the largest number of specialist opium traders with around 200 shops in the bazaar selling only opium. There was also general agreement that Sangin has a higher turnover of opium than any other bazaar in the south, followed by Musa Qala. District bazaars in KaJaki, Nowzad and Maiwand were considered significantly smaller than Sangin and Musa Qala both in terms of turnover and numbers of specialist traders. Nevertheless, respondents and key informants reported that cross-border traders from Iran and Pakistan frequently visited these smaller bazaars to purchase opium directly.

Respondents in the south indicated that the trade in opium is competitive at all levels but not aggressively so. Indeed, where transactions were considered mutually beneficial traders are reported to cooperate on a inter and intra district basis. A number of examples of large shipments of opium consisting of contributions from numerous traders in the bazaar were cited by those interviewed. For instance, it was reported by a number of respondents that a group of traders had experienced financial problems as a result of a continuing delay in the payment for a large shipment of opium by Baloch traders. To both assist in resolving their financial problem and to incur the final benefits of the deal, a number of traders from Musa Qala agreed to pay the Sangin traders an amount equal to the value of the opium at the time that it was sold.

Yet, there were reports that intense competition between some of the major traders in the southern region had resulted in violence with attacks on caravans of opium by rival traders. However, it was suggested that such incidents were rare and on the whole the trade within southern Afghanistan was peaceful.

7. CostsRespondents in the east considered the costs associated with the opium trade as negligible, comprising only of local transport costs, including taxi or bus fares. Similarly, the majority of traders in the south indicated that the costs they incurred were minimal. Indeed, to further minimise costs most of the respondents in the south had used the income they had earned from their trade in opium to purchase a car or motorbike for transportation.

Most of the opium traders interviewed in the south operated out of rented shops in the bazaars, whilst some traded opium directly from their houses. Generally each shop was furnished with a standard set of equipment, including (i) a heater with metal plate and knife for testing the quality of opium; (ii) polythene sheeting and bags for drying opium; (iii) plastic and metal bowls for storing the opium; (iv) metal boxes for storing money and other valuables; (v) scales and weights; and (vi) a large metal container for boiling wet opium with water.

Other costs cited included wages for employees, including security guards and the specialist in weights and measures, known as the tarazoo dar. The payment for both security and thetarazoo dar tended to be shared between neighbouring shops with the tarazoo dar receiving a commission of less than $0.10 cents per kg of opium weighed. A number of traders in the south also indicated that they paid tax on their income, known as zakat, to the district administrator, or woliswol.

8. Increasing profits through the provision of advances

Over 60% of all respondents provided cash advances to farmers on their future opium production. Whilst this system of advance payments, known as salaam, operates for a number of different agricultural products, including wheat and black cumin, opium is the preferred crop of lenders.5/

Respondents indicated that the provision of salaam to farmers was dependent on their personal cash-flow. Almost half the traders interviewed in the east, indicated that in the period when farmers most require advances, prior to planting in October/ November and during the winter months, they themselves did not have cash surplus to their own needs. This was perceived as unfortunate by these traders as they believed that the provision of advances would substantially increase their profit margins on opium trading. Only one respondent in the east and two respondents in the south indicated that they thought the provision of advances was un-Islamic.

Those that provided advances in the east were generally shopkeepers. Over 60% of the traders interviewed in the south provided advances, the amount of opium they traded varied from 2.2 mt to 20 mt. In the south, respondents reported that the advance system can operate at all levels of the opium trade, sometimes connecting cross-border trader in Iran or Pakistan to opium poppy cultivator in southern Afghanistan.

All of those respondents in Shinwar and Achin who reported providing advances in January paid an advance of $26.00 per kg to those farmers considered trustworthy and only $20.80 per kg to those who were considered a risk. One shopkeeper highlighted the risky nature of this system claiming that one of his risky farmers had absconded with his and other shopkeepers money. Respondents who provided advances reported selling the opium they bought on advance for $20.80 to $26.00 per kg, at a rate of $47.80 to $76.00 per kg. As such traders who provided advances reported a mark-up of $21.80 to $55.20 per kg compared to only $3.00 to $9.00 per kg for those with limited cash-flow.

In the south , respondents indicated that salaam had generally been given at a rate of $12.70 to $19.00 per kg in January 1998. Given a post harvest price of $60.30 to$62.20 per kg, traders had the opportunity to earn significant profits on the opium they purchased in advance. However, there were numerous reports of recipients of salaam payments failing to repay their debts in full due to the poor harvest in many areas in 1998 and a number of incidents where recipients simply absconded.

Whilst it was generally recognised that salaam provided traders with the opportunity to significantly increase their profit margins, most expressed some caution regarding the number of advances they offered. Generally, respondents reported offering salaam to a few trusted individuals. Indeed, of those respondents who offered salaam in the south, only one trader received more than 5% of his total trade in opium through salaam payments. This particular respondent was reported to be one of the largest opium traders in Musa Qala, purchasing approximately 9 mt of opium per annum, and providing advance payments on approximately 15% of his total trade.

Those respondents that provided advances in the east suggested that it was not essential for a farmer to grow opium to obtain a loan, however repayment should be made in opium. In the south, respondents indicated that they only provided salaam to those involved in the cultivation or trade of opium. However, given the predominance of specialist opium traders amongst those interviewed the emphasis on opium cultivation and trade as a condition for lending should be of little surprise.

Respondents indicated that the size of the advance depended on the month and the ?trustworthiness? of the farmer. In Shinwar and Achin respondents indicated that those farmers that were known to the shopkeeper and known to produce opium obtained a preferential rate compared to those requesting an advance for the first time. In the south ?trustworthiness? was defined by respondents in terms of whether the individual and his family were known in the area, whether they owned land, and whether the opium that they had previously repaid in return for salaam was of good quality.

Indeed, a number of respondents in the south suggested that they did not give salaam due to the quality of opium that they had received as payment in the past. Other respondents suggested that in order to ensure that they received good quality opium in return for salaamthey wrote the name of the debtor on the polythene bags in which it is kept. If the quality was found to be poor, the opium is returned and a cash payment is demanded.

�Those respondents providing advances viewed them as a service to those households enduring hardship. Respondents indicated that advances were provided on the basis of need and were available to both landowners and the landless. Those shopkeepers that provided advances indicated that whilst advances were generally requested by poorer households, wealthier members of the community also took advances for household emergencies.

If debts could not be repaid in opium due to a failed harvest, some traders indicated that they would take back the same amount as advance in cash. These tended to be small traders who insisted that they did not have the cash flow to delay the payment until the following year. However, some of the larger traders in the east, including the shopkeepers indicated that those advances that were not repaid at harvest would require repaying at double the amount of opium the following harvest.

In the south, a number of respondents suggested that the failure by some sharecroppers to repay their salaam payments was not viewed as particularly detrimental, claiming that inexpensive and ?trustworthy' sharecroppers were scarce and that ongoing debts would ensure that they did not relocate.

5/ For a more detailed account of local informal credit systems in Afghanistan see UNDCP'sStrategic Study 3: The Role of Opium as a Source of Informal Credit, October 1998.

|

|

|

9. Increasing profits through the commission systemIn the east, those traders that were not in immediate need of cash reported entering into agreements with shopkeepers in Ghani Khel to sell their opium. Respondents indicated that these agreements are based on the traders assumption that opium prices will rise. The shopkeeper is responsible for storing the opium and finally selling it at the highest possible price. The charge for this service is a commission of $0.08-$0.16 per kg to both farmgate opium trader and the final buyer.

Respondents indicated that this arrangement relies on trust between the farmgate opium trader and the shopkeeper as, not only does the price of opium fluctuate, but the opium will dry over time, altering the final weight and subsequent value of each chakai, or cake, of opium. Whilst most farmgate traders who were in immediate need of cash reported selling their opium to the highest bidder in Ghani Khel bazaar, those that used the commission system used the same shopkeeper over a number of years.

Respondents indicated that the commission system operating in the east also allows traders to spread the risks of robbery and interdiction, storing the bulk of their opium with trusted shopkeepers in Ghani Khel whilst retaining a limited supply of opium in the house for emergencies.

However, it is important to note that respondents interpretation of ?commission' differed between the east and south. In the south, respondents referred to commission in terms of the contracting and often sub-contracting of traders to purchase opium. This contractual arrangement between traders was reported to operate at all levels of the opium trade. Indeed, numerous examples of bulk orders of opium made by cross border traders were cited in the bazaars of Kajaki, Kishke Nakod, Musa Qala, Nowzad, and Sangin. Respondents indicated that where these orders could not be satisfied with existing stocks of opium, large traders might commission a number of smaller traders in other bazaars to meet the order. Again where existing stocks failed to meet the amount of opium ordered each of these traders would in turn, commission a number of individuals to purchase the opium from neighbouring districts and provinces.

Respondents reported that the payment on commissioned orders may be on delivery or in advance depending on the cash flow of those involved. For instance, in Nowzad a respondent reported that he had received a pre-harvest order for 270 kg of opium from an opium trader in Sangin, receiving the total payment of $5,940, or $22.00 per kilogramme, in salaam. To purchase the opium required, the respondent contracted a number of farmgate traders, offering them a salaam payment of between $16 to $19 per kg. These farmgate traders subsequently bought 180 kg of opium prior to the harvest from 30 separate households at a price of $12.50 to $16.00 per kg. However, with the poor harvest in 1998, only 3 of the 30 households that received the advance were able to repay the opium they owed in full. In order to improve his relationship with the trader in Sangin the respondent elected to repay the opium he owed in full, at some financial loss to himself. He believed that this strategy would strengthen the relationship between the traders, resulting in larger and more regular purchases in the future.

Respondents indicated that they only contracted farmgate commission agents during the winter months or when they had received bulk purchase orders from cross-border traders. Indeed, most respondents in the south reported that during the harvest period, those with opium traveled to the bazaar to sell. However, during the winter when the supply of opium is reportedly more scarce, and what is available is in the hands of the relatively wealthy, traders were required to travel to the villages to purchase opium. Although many of the traders utilised family labour for this task, those that traded in large amounts of opium contracted this function to ?trusted? individuals. All respondents indicated that trust, particularly when advance payments were made, was essential to the business relationship between trader and farmgate commission agent.

Whilst the vast majority of respondents indicated that they only contracted one or two commission agents to purchase opium at the farmgate, one trader claimed to contract up to 20 farmgate commission agents in order to satisfy some of the bulk purchase orders from Baloch traders. This particular individual was reported to be the largest opium trader in Musa Qala.In the south only one respondent indicated that he was familiar with the commission system operating in Ghani Khel bazaar. This particular trader was taking commission of $1.20 to $3.20 on each kilogramme sold from his shop. He did not consider this to be particularly profitable, preferring to purchase opium in advance through salaam. However, his financial situation, arising from the theft of approximately 2700 kg of opium by Baloch traders, had left him little choice but to sell opium for commission.

10. Increasing profit through selling at the border

Respondents in Helmand and Qandahar indicated that an increasing number of traders were transporting opium directly to the border with Pakistan, Iran and Turkmenistan to increase their profit margins. Of those interviewed in the south almost 25% transported opium to the border areas.

The border price of opium was reported to increase to $73.00 per kg for the best quality wet opium and approximately $95.00 per kg for the best quality dry opium. However, those interviewed indicated that the border market is highly competitive with numerous cross-border traders offering marginally different prices according to the prevailing supply and demand at the time. The costs cited for transporting opium to the border ranged from $1.20 to $1.80 per kg.

The majority of respondents indicated that opium was dried prior to its transportation to the border. Two methods of drying were cited, the first which could often be seen in the bazaars, was to spread wet opium on a polythene sheet and dry in the sun; the second was to boil the opium in a metal container with water. It was suggested that dry opium was both easier to transport and had less odor than wet opium. Once dried, key informants and respondents involved in transporting suggested that opium was often separated into one kilogramme blocks, wrapped in polythene and covered in cloth ready for its final transportation across the border.

A number of respondents in the south claimed that they had been involved in transporting large amounts of opium to the border, including one shipment of 2 mt and another of 3 mt. It was widely recognised that the actual cross-border trade was a risky endeavour with the threat that traders from Iran and Pakistan would fail to return and pay for opium they had received in advance. However, once across the border respondents suggested that the value of the best quality dry opium was the equivalent of $126.00 at the time of fieldwork.

|

|

|

11. Incurring lossesDespite the reported profitability of the opium trade all respondents indicated that they had made losses on opium trading both in the initial years of trading due to inadequate knowledge regarding the quality of opium, and throughout their trading career due to deceptions, the rapidly fluctuating price of opium, and the changing value of the Afghani.

The majority of traders in the east reported that they had suffered losses during the initial years of trade due to purchasing poor quality opium. Traders reported that there are three qualities of opium in Nangarhar: Spin, barani and sur. Both spin and barani are considered poor quality, the former affected by excess groundwater and the latter by rainfall during its collection. At the time of fieldwork spin and barani opium were selling in Ghani Khel for $27.00 per kg. Sur or red opium is considered high quality and was earning approximately $55.50 per kg at the time of the fieldwork. The quality of sur is denoted by its consistent dark red or brown colour and its sticky texture.

Respondents in the south referred to the different qualities of opium in the south as tor (black), sur (red) and jar(yellow). At the time of fieldwork the highest quality opium, tor, sold at the farmgate for between $60.30 to $62.20 per kilogram, whilst the poorest quality, jar opium, was being bought at the farmgate for the equivalent of $44.00 per kg. The best quality dry opium was being bought for $82.50 per kg. Respondents indicated that there is a preference for storing opium wet in polythene bags of 4.5 kg in the south. The reasons for this were varied, including the high moisture content of opium in the south, the preference for retaining the weight of opium for selling purposes, and the comparative profitability of wet and dry opium.

There was general consensus amongst both respondents and key informants that the best quality of opium was obtained from the first lancing of opium poppy that is grown in high dry areas. It was suggested that the opium produced from subsequent lancings had a higher water content. There was also agreement that areas with a high water table such as those near rivers or canals typically produce lower quality sur/spinand jar opium. There was general consensus amongst both respondents and key informants that the best quality of opium was obtained from the first lancing of opium poppy that is grown in high dry areas. It was suggested that the opium produced from subsequent lancings had a higher water content. There was also agreement that areas with a high water table such as those near rivers or canals typically produce lower quality sur/spinand jar opium.

In the south it was suggested that by carefully mixing poorer quality opium with that of a higher quality it was possible to disguise poor quality opium and sell it at higher price. Respondents indicated that this was a particularly skilled job and was most commonly undertaken with sur and jar opium.

Moreover, traders also reported that adulterants were added to opium by cultivators and traders alike. In Nangarhar the locally produced black sugar known as gur, raisins and rice flour are reportedly added to opium to increase its value to weight ratio. Adulterants of wet opium cited by respondents in the south, included black tea and Diammonium Phosphate and sugar boiled in water.

Given the prevalence of mixing the different qualities of opium the use of adulterants, testing the quality of opium was seen as a pre-requisite by respondents in both the south and east. Testing was seen as particularly important when respondents purchased from opium cultivators and traders who they were not familiar with.

Three methods of testing opium were cited by respondents. The first test referred to by traders in both the south and the east involved smearing the opium on the hand and checking the consistency and texture of the opium to test for adulterants. In the heat of the sun the opium can be rolled-up and returned to thechakai or bag. The second test consisted of spreading the opium on a metal plate with a knife and heating it over a flame, thereby removing all the moisture from the opium. The opium was then scraped onto the knife and heated once more. Respondents indicated that the number and type of the bubbles this final heating produced denoted the quality of the opium. The final test involved pressing the knife with the heated opium firmly against a cloth and slowly drawing the knife away. The heated opium fixes itself to the cloth producing strands of opium between both the knife and the cloth. Respondents suggested that the longer and more numerous these strands the higher the quality of the opium.

A number of respondents in the southern region reported making significant losses. Few of the traders admitted to making losses on purchasing poor quality opium, suggesting they were too skilled in identifying the different qualities of opium to be deceived. However, reports of significant losses were reported by respondents involved in selling opium at the border with Pakistan and Iran.

The most obvious losses emanated from deceptions where cross-border traders agreed to pay a higher price if they were allowed to take the opium across the border and return to pay after an agreed time period. Once across the border with the opium, the trader was not seen again. A number of respondents had experienced this deception. For instance, one respondent had lost almost 3 mt of opium to three cross-border traders. To try and regain his lost opium, or the money he was owed, the respondent had kidnaped two family members of the cross border traders involved.

The majority of those involved in selling opium at the border reported suffering losses as a consequence of fluctuating exchange rates. Respondents indicated that the relatively high price of opium, the use of the Iranian toman and Pakistani Rupee for payment at the borders, and the growing strength of the Afghani, had led many traders to take a more cautious approach to trading. Indeed, there was great concern that the continued strengthening of the Afghani would result in traders receiving a lower real price at the border, after converting tomans and rupees to Afghanis, than respondents had initially paid at the farmgate. The majority of those involved in selling opium at the border reported suffering losses as a consequence of fluctuating exchange rates. Respondents indicated that the relatively high price of opium, the use of the Iranian toman and Pakistani Rupee for payment at the borders, and the growing strength of the Afghani, had led many traders to take a more cautious approach to trading. Indeed, there was great concern that the continued strengthening of the Afghani would result in traders receiving a lower real price at the border, after converting tomans and rupees to Afghanis, than respondents had initially paid at the farmgate.

Similarly, in the east the rapidly fluctuating price of opium meant that all the traders had incurred losses, selling opium at a lower price than which they bought it. Although traders recognised that retaining the opium until the price rose would allow them to avoid such losses, the majority indicated that they could not delay the sale of opium due to their immediate cash requirements.

Even those farmers that had provided advances to farmers reported making losses. The majority of occasions that losses were incurred related to a dramatic fall in the price of opium at harvest time, resulting in the level of advance exceeding harvest prices. However, a number of traders also reported that they had experienced a number of defaulters. Although most of these defaulters had repaid the following year at twice the rate agreed at the time of the advance, one farmer had never repaid his debts and the matter was being determined by the jirga in his absence.

|

|

|

12. The intra-regional mobility of tradersAll the respondents indicated that their mobility within the eastern region was not constrained. However, discussions regarding inter-regional mobility provoked a variety of responses from farmgate opium traders.

In Achin and Shinwar all the opium traders interviewed suggested that they did not purchase opium from the South, despite its traditionally lower price as a consequence of the poor quality of the opium from that region. It was a unanimous view that the opium in the South was generally of the spin variety and was not in high demand from large traders and processors. The explanation offered for this was that the use of spin opium in the production of heroin led to a grey-coloured final product that was unpopular with consumers in the West.

Further discussions revealed that respondents did feel constrained from traveling to the southern region to purchase opium. Primarily the reasons offered were financial with respondents indicating that a journey to the south would only be viable if significant quantities of opium were bought. It was suggested that this required financial resources that were not at the disposal of smaller traders. This was highlighted by the claim that for the first time a major trader from Shinwar had arranged the transportation of a large quantity of opium in consultation with a trader in Qandahar in 1997.

Aside from the financial constraints a large number of traders also indicated that they were unfamiliar with the Southern region, had few contacts in the area and would feel ?nervous' purchasing opium in the Qandahar and Helmand.

In the south, all respondents indicated that there were no restrictions on trading in opium in other districts or provinces. Whilst all the traders interviewed in the south tended to focus the bulk of their trading on neighbouring districts, most were willing to travel further afield when local supplies were scarce or prices more competitive

There certainly appeared to be few restrictions on the opium trade in the southern region. Opium could be seen drying in the sun in all the bazaars visited. Moreover, many of the shops trading in opium were open fronted and given their location in the district centres, close to the district administrators, orwoliswals, office. Indeed, one respondent, a trader of 25 years, indicated that restrictions on the opium trade in the past had prompted him to conduct his business from his house. However, growing confidence had led the respondent to rent a shop and trade in opium openly in the bazaar.

A few examples were given of opium from the south being transported and sold in the eastern region. These examples usually involved a number of traders, each contributing a proportion of the total amount of opium required. However, it was generally felt that, although there were no restrictions on such trade, it rarely proved profitable.

Yet, despite the claims of improved security and the freedom of trade a number of respondents did suggest that there had been a number of incidents where convoys of opium had been attacked. Respondents and key informants indicated that these cases tended to be amongst the bulk cross border traders.

13. Security as the most significant change in the opium trade

The majority of those interviewed in Shinwar and Achin reported that they had been trading in opium for 3 to 5 years. None of those interviewed indicated that taxes were imposed upon their trade. When questioned none of the respondents indicated that they had suffered financially or physically due to robbery. Indeed, all the respondents suggested that physical security was currently not a problem. This was highlighted by all respondents as the most significant change in the nature of the opium trade over the last few years. For those traders that had been trading in opium for ten years, both security and considerable increases in the number of farmgate traders were cited as the most significant changes they had experienced in the opium trade.

Similarly, in the south the increase in the number of traders was most commonly cited as the most significant change in the opium trade over the last ten years. However, the improving security situation was also considered of great importance by the majority of respondents and key informants in the south.

14. Trading in opium and social mores

None of the respondents in the east indicated that they perceived trading in opium as conflicting with current social mores. The buying and selling of opium appeared to be undertaken by all those who had sufficient cash-flow during harvest time. Moreover, while one respondent in the east indicated that advances were un-Islamic he saw no conflict between the opium trade and his religious obligations.

In Ghani Khel and Kahi it was possible to see a number of shops which specialise in the buying and selling of opium, conducting business behind the cover of a curtain. In the bazaars in the more remote parts of Achin, opium was traded more openly. Indeed, children, both male and female, as young as 10 were witnessed selling opium in a number of these local bazaars in Achin district.

However, respondents did see a divide between trading in opium and the processing and trading of heroin with the large majority of respondents finding the latter socially unacceptable. Whilst all the respondents indicated that processing required investment costs that were beyond their financial capacity, only one respondent indicated that he would engage in heroin processing if he had the resources. Key contacts were also cited as a pre-requisite to diversifying into heroin processing and trading. Respondents indicated that they personally did not have access to the ?right people' with either the knowledge of the production process, or the influence to ensure processing and trading could be undertaken without restriction.

Perhaps surprisingly, the vast majority of respondents in the south believed the opium trade to be un-Islamic. Yet despite this almost 85% of those interviewed in the south had performed Haj and two were in fact mullahs. Two respondents in the south considered the provision of salaam as un-Islamic.

15. The coping strategies of opium traders

None of the respondents believed that the opium trade would end imminently. Consequently, none of the small traders interviewed saw the need to act against UNDCP's efforts to eliminate opium cultivation.

Similarly, few respondents in the south believed that the trade in opium would be banned by the local authorities. Indeed, only one respondent who was a specialist opium trader had diversified his business, electing to trade in both fertiliser and opium in anticipation that the trade in opium may be banned in the future.

Respondents in the south indicated that the opium trade is an integral part of the local economy, providing a significant source of income for a large proportion of the population. As such, respondents believed that a ban on the trade in opium would have negative consequences for local trade and industry that are not directly linked with the opium trade.

Increasing demographic pressures and the lack of viable income earning opportunities for those with an education was cited as the primary motivations for trading in opium. Respondents indicated that without alternative income sources for those with an education the authorities could not ban the trade in opium. A number of respondents suggested that attempts to ban the trade without providing alternatives would result in a growing antagonism between the population and the local authorities.

There was also a general consensus amongst respondents in the south that Afghans earned very little from the illegal drug trade and that the greatest proportion of profit was accrued by khariji, or foreigners. This perception exacerbated the resentment that respondents felt towards attempts to ban the trade in opium.

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. Findings

- The structure of the opium trade differs markedly between the eastern and southern regions. It would certainly appear that the process of centralisation in the east has led to short term price differentials with the lowest farmgate prices occurring in those areas located the furthest distance from the dominant opium market in the eastern region, Ghani Khel. These price differentials appear to have created a class of short term, speculative farmgate traders that during the opium harvest exploit their proximity to Ghani Khel to travel to outlying districts and provinces where the inhabitants are either not fully aware of any increase in the price of opium, or, are unwilling to travel to Ghani Khel due to travel costs rendering the sale of small amounts of opium unprofitable.

- The geographic location of Ghani Khel, would appear to be a determining factor in the dominance of Ghani Khel in the opium trade in the eastern region. Ghani Khel is located centrally, both logistically within the eastern region, and politically within the Shinwari tribe. Indeed, key informants report that prior to the war and Ghani Khel's dominance, Kahi bazaar in Achin district was the centre of the opium trade in the eastern region. The significance of Kahi was a consequence of its central location in the loya woliswoli, or greater district, of Shinwar, consisting of Deh Bala, Achin, Nazian, Durbaba and Shinwar, all traditional opium growing districts. The regional centre for the greater district of Shinwar was in Ghani Khel, where a significant government presence was maintained. Within the greater Shinwar district, Kahi retained a degree of autonomy from the authorities, allowing the opium trade to exist without interference. With the conflict in Afghanistan and the breakdown in the rule of law and civil administration, the regional centre for the opium trade appears to have shifted to Ghani Khel. Moreover, when viewed within the context of the expansion to the north in the area cultivating opium poppy, it would appear that Ghani Khel is better placed both geographically and logistically than Kahi due to its proximity to the asphalt road.

- The influx of large traders to Ghani Khel, purchasing significant amounts of opium for processing within Afghanistan would appear to consolidate the centralisation process in the east. The commission system operating in Ghani Khel also strengthens the bazaars central role in the eastern opium trade, providing the necessary incentive to ensure that those purchasing opium trade and store their opium in Ghani Khel. As such the commission system ensures a steady supply of opium is maintained in Ghani Khel bazaar to meet the demands of large traders.

- In the south, the presence of numerous buyers and sellers have led to a more decentralised and ?free' market structure. Opium prices would appear to vary little between districts and provinces. Consequently there is little economic advantage in traveling between regions. The evidence of a low mark-up on opium in the southern region is supported by the high incidence of mixing of the different qualities of opium, the addition of adulterants, and the increasing evidence of farmgate traders transporting opium to the southern and eastern borders. All this would tend to suggest that where possible opium traders, like traders in any business are continually pursuing strategies to increase the returns on their trade and offset the losses that they are incurring. Moreover, reports suggest that prior to the war Musa Qala played a central role in the opium trade in the southern region. However, insecurity in the area due to conflict within the mujahiddin movement prompted traders to relocate their operations to Sangin. With improved security and the demise of the factionalism of the commanders, Musa Qala has once gain emerged as an important opium bazaar in the southern region. However, in the south a number of other bazaars have also developed direct links with Baloch traders from both Pakistan and Iran, resulting in a more decentralised market structure.

- The opium trade in the eastern region shows evidence of vertical integration on the basis of tribe rather than a well organised formal institutional structure. Traditionally the cross border trade has been associated with particular tribal groups that span Afghanistan's borders with its neighbours in the south and east. In the south, numerous Baloch tribes are reported to be heavily involved in the cross-border trade in opium, whilst Pashtoon tribes have traditionally focused on opium poppy cultivation and the trade within Afghanistan. In the east, Shinwari Pashtoons have not only traditionally cultivated and traded opium, but through their links with Afridi Pashtoons on the other side of the border, have developed a virtual monopoly on the processing and final transportation of heroin into Pakistan. Whilst the sheer number of Baloch tribes in the cross border trade has facilitated a process of decentralisation, with numerous bazaars emerging as important international markets for opium within the southern region.